In 1932 George Balanchine happened upon a ballet protégée, Irina Baronova, when she was a 12-year-old pupil of Olga Preobrajenska, the Russian ballerina teaching in exile in Paris. The visionary choreographer, who throughout his career would repeatedly mentor and package outstanding female dance talent, bundled Baronova with two equally precocious ballet cohorts, Tamara Toumanova (12) and Tatiana Riabouchinska (14), as “Baby Ballerinas.” With each young lady contributing her own unique strengths and qualities, the trio was a huge audience-pleasing phenomenon in the ballet boom of the mid-twentieth century. Those were the days … when the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, with artistic roots on the exotic Côte d’Azur, took the dance world by storm.

Following this auspicious start, Baronova continued in her rich career with the Ballet Russe, one of several offshoots of Diaghilev’s original troupe (it closed for business in 1929). The company’s mad, crisscrossing train tours of the United States during the war years is marvelously recounted in the 2005 film, Ballets Russes. (Baronova is much featured in this documentary.)

Following this auspicious start, Baronova continued in her rich career with the Ballet Russe, one of several offshoots of Diaghilev’s original troupe (it closed for business in 1929). The company’s mad, crisscrossing train tours of the United States during the war years is marvelously recounted in the 2005 film, Ballets Russes. (Baronova is much featured in this documentary.)

Now we have the opportunity to dig deeper — and there’s a touching personal connection involved. Actress Victoria Tennant, daughter of Baronova, has organized her mother’s photo collection into a slide show presentation, an evocotive capture of a precious and unique life in dance. She’ll give the presentation Saturday October 18 as part of the spoken word series at the Center for the Art of Performance at UCLA.

Baronova, a blonde ball of fire, was praised by Anna Kisselgoff in the New York Times for her “vivacious wholesome beauty, indelible classical style and virtuosic technique.” Engaged by impresario Colonel W. de Basil for his Monte Carlo troupe from 1932-39, Baronova danced in creations by Léonide Massine and Balanchine. She performed with the newly constituted American Ballet Theatre in the early forties, then with Sergei Denham’s Ballet Russes de Monte Carlo and finally with a Massine-led company.

Baronova was a creator in Massine’s great masterpiece, “Les Présages” (1933), set to Tchaikovsky Symphony Five, an infamous symphonic ballet that blew this dance critic away when the Joffrey Ballet restaged it in 1993.

The inheritor of a massive trove of dance memorabilia, Tennant combed through thousands of photographs to create her program. Her research covered piles of letters dating to 1926, crumbling press clippings and posters. The St. Petersburg-born Baronova, who spoke Russian, Roumanian, French and English fluently, died in Australia in 2008. However, noted her daughter in a phone conversation, “She was a refugee all her life, with no home. She lived on the road out of a suitcase.”

The inheritor of a massive trove of dance memorabilia, Tennant combed through thousands of photographs to create her program. Her research covered piles of letters dating to 1926, crumbling press clippings and posters. The St. Petersburg-born Baronova, who spoke Russian, Roumanian, French and English fluently, died in Australia in 2008. However, noted her daughter in a phone conversation, “She was a refugee all her life, with no home. She lived on the road out of a suitcase.”

“She wrote her own story in her biography. I’m telling her story in images. The photos are rare. They are not typical publicity photos, taken for the public. They are private photos of dancers taken by dancers. Many of the photos were by my grandfather, who was an artist and scenic designer.

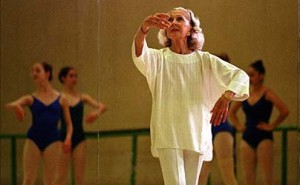

“There are pictures of dancers on the beach, performance pictures taken from the wings, rehearsal photographs.”

One of Tennant’s very favorite images captures a backstage moment. “There’s my mother on the night of a gala opening. She’s slumped in an arm chair [exhausted]. She is pictured with [British dance critic] Arnold Haskell, dressed in white tie and tails.”

One of Tennant’s very favorite images captures a backstage moment. “There’s my mother on the night of a gala opening. She’s slumped in an arm chair [exhausted]. She is pictured with [British dance critic] Arnold Haskell, dressed in white tie and tails.”

The book is a hybrid, according to Tennant: “It’s a memoir; it’s a ballet history; and it’s a photography book.”

The actress and her mother were close. “I spoke with her, toward the end, every day and an hour before she died. She was an extraordinary mother, everything she did was at 110%.”

In a way, Baronova was perpetually the baby ballerina. It was a challenge, admitted Tennant, “being the child of a child.”

In a way, Baronova was perpetually the baby ballerina. It was a challenge, admitted Tennant, “being the child of a child.”

“Most of us start as children and advance toward adulthood one step at a time. My mother became a great star at age 13. On stage, Irina Baronova knew her value in the company, but on the outside she was a child under the complete control of her parents.

“She was charming, loveable, honorable, and she had a child’s sense of delight. She was emotionally fresh and available in a way that children are. She was smart and cultured but she wasn’t fully an adult. She remained a little girl and a great artist simultaneously.

Baronova was a model to Tennant as she nurtured her own artistry as an actress. “She gave me a living example. She worked so hard and was so committed to what she did. She lived a highly regimented life, between her parents and the company, which was run like the army. With her, work ethic came first.”

Victoria Tennant: Irina Baronova and the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo | Little Theater at Macgowan Hall | Sat Oct 18, 4 pm