From Sacramento to San Diego, California’s Mexican and Spanish underpinnings are as historic as they are pervasive. We often take those connections for granted, but LACMA’s exhibition “Found in Translation: Design in California and Mexico, 1915-1985” offers a fascinating view of the influence and confluence between the two cultures in the 20th Century. It’s part of the Getty Foundation’s “Pacific Standard Time LA/LA” blitzkrieg currently carpet-bombing SoCal art institutions.

The show assembles some 250 objects, furniture, textiles, couture, paintings, murals, sculpture, drawings, ceramics and ephemera. It’s especially effective in showing the ways that Mexican design has manifested in Los Angeles.

The Panama-California Exposition of 1915 ignited the taste for elaborate Spanish Baroque building style. Although seen throughout the state, Spanish Revival was most visible in Southern California. The Mediterranean climate imbued red tile roofs, adobe-colored stucco and wrought iron with a relaxed pueblo aura as Los Angeles grew into a Metropolis.

The style conjured nostalgia for an imagined era. Early Hollywood often mythologized old Spanish days: three silent movie excerpts depict idealized reveries with Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford and Delores Del Rio. Like Tarzan, Zorro movies continually regenerate.

Wallace Neff designed mission casas for Hollywood stars, but Frank Lloyd Wright’s L.A. homes found inspiration in pre-Hispanic structures. A concrete finial from the Hollyhock House (’19) and a plan for his Ennis House (’24) invoke a Mayan temple. Likewise, Batchelder and California Clay cranked out picaresque Mayan designs on tile.

Wallace Neff designed mission casas for Hollywood stars, but Frank Lloyd Wright’s L.A. homes found inspiration in pre-Hispanic structures. A concrete finial from the Hollyhock House (’19) and a plan for his Ennis House (’24) invoke a Mayan temple. Likewise, Batchelder and California Clay cranked out picaresque Mayan designs on tile.

A rustically regal wood and leather chair must surely come from some old hacienda. Nope — it’s from the Monterey line by Barker Brothers (‘30). And a hand-tooled leather saddle with silver trimmings connotes the Rose Parade as much as el rancho grande.

Nationalism spurred Mexico to embrace its ancient heritage. Elites like Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo collected pre-Columbian artifacts. In L.A., the impulse surfaced in the elaborate facades of downtown L.A.’s elegant Mayan Theatre (’27) and the surreal Aztec Hotel in Monrovia (’24). But by the ‘30s, California Colonial was all the rage with Mexican architects. What Americans borrowed, they retrieved, associating it with prosperity. Then, as now, America signified abundance.

For European émigré artists who settled in SoCal in the ‘30s and ‘40s, a jaunt south of the border was de rigueur. Mexican artists and architects, eager to drink from the fountain of modernism, took on Euro-trappings in their own work. Alfredo Martinez’s study, “Head of a Nun” (’34), is a simplified planar rendering that looks straight out of the Bauhaus. Richard Neutra as much influenced Mexican modernists as California architects.

For European émigré artists who settled in SoCal in the ‘30s and ‘40s, a jaunt south of the border was de rigueur. Mexican artists and architects, eager to drink from the fountain of modernism, took on Euro-trappings in their own work. Alfredo Martinez’s study, “Head of a Nun” (’34), is a simplified planar rendering that looks straight out of the Bauhaus. Richard Neutra as much influenced Mexican modernists as California architects.

Mexican native Martinez’s relationship with America points to a number of complexities. Like all the Mexican muralists, he was critical of the U.S. But William Randolph Hearst’s mother paid for his study trip to Europe, and he moved to L.A. to seek medical care for his daughter’s rare bone disease. Martinez had a number of high-profile SoCal shows and commissions—including a 100-foot mural underwritten by artist Millard Sheets.

Mexican influence on mid-century americanos surfaced in surprising ways. Ruth Asawa’s wire sculpture (’61) looks like nothing so much as a Mexican fountain. Charles and Ray Eames reveled in colorful Mexican crafts in their “Day of The Dead” mini doc (’57). Marilyn Neuhart’s folksy-but-sophisticated dolls could be source material for Disneyland’s Small World.

After Mexican independence in 1821, Aztec warriors symbolized a strong state. The Mexican muralists picked the motif up in the ‘40s, and Chicano graphics of the early ‘70s often depicted the bloodthirsty Aztecs and Mexican revolutionaries.

Wall copy tells us that the zoot suit on display found favor with Mexican gangs south of the border. It was the uniform of their pachuco cousins, but the term came from Duke Ellington’s 1941 musical “Jump for Joy” at downtown’s Mayan Theatre. As Duke once asked: Just who is basking in the shadow of whom?

Wallace Neff, Arthur K. Bourne House, Palm Springs (exterior perspective), 1933, The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, California

Batchelder-Wilson Company, Maya design tiles, c. 1923–32, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, purchased with funds provided by Patricia M. Fletcher, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Ruth Asawa, Untitled (S.266), 1961, Collection of Snyder Family Living Trust,© Estate of Ruth Asawa, photo by Paul Hassel

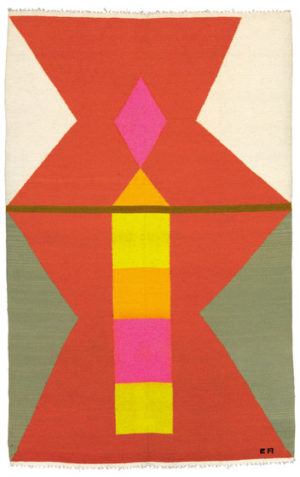

Evelyn Ackerman for ERA Industries, Launch Pad tapestry, designed 1970, Collection of Jerome Ackerman,© ERA Industries/Evelyn Ackerman, photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Kirk Silsbee publishes promiscuously on rock, jazz and culture.

More from Silsbee: Parks & Wrecks: Carlos Almaraz @ LACMA

Found in Translation: Design in California and Mexico, 1915-1985 | LACMA Resnick Pavilion | thru April 1 2018

I always love reading Silsbee’s beautiful and informative essays. He never falls into the trap of some arts writers who tell us more about themselves than about their topic.