We’re always looking for good show-biz stories involving the estimable Dolores Gray. Jack Cole, who worked with Gray on several projects — Kismet, Designing Woman among them — had a few select words about Gray … and her mother.

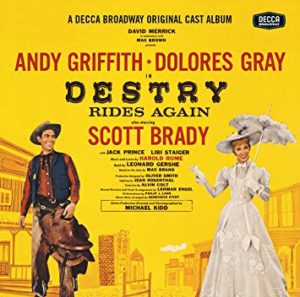

In this case, the story concerns Gray’s hiring for Destry Rides Again, the Broadway musical adaptation of the James Stewart/Marlene Dietrich movie. The musical was produced by (“Mr. Misery”) David Merrick.

In this case, the story concerns Gray’s hiring for Destry Rides Again, the Broadway musical adaptation of the James Stewart/Marlene Dietrich movie. The musical was produced by (“Mr. Misery”) David Merrick.

Merrick simply needed Gray for this role. That’s because Ethel Merman, the only warbler who could out belt Gray’s formidable singing chops, was otherwise occupied. The Merm was preparing Gypsy, which would open soon after “Destry,” outrun it by twice the duration, and overshadow it.

In a classic old-school producer’s lie, Merrick, in wooing Gray to sign opposite musical-newbie Andy Griffith, promised his leading lady, who was not a trained dancer, that she could participate in a big production number choreographed by Michael Kidd — also the show’s director. Gray’s instinct to get that promise in writing was assuaged by the slippery producer’s insistence that she take him at his word. Do not trust him, Dolores!

This story about the “whip dance” is excerpted from Howard Kissel’s David Merrick: the Abominable Showman (1993):

[quote] Gray told Merrick she could only be in the show if she were included in what promised to be its choreographic high point, a whip dance … Even if she participated in the dance for only four bars, she told him, it would give her character a darker color than that of being simply a saloon hostess.

[quote] Gray told Merrick she could only be in the show if she were included in what promised to be its choreographic high point, a whip dance … Even if she participated in the dance for only four bars, she told him, it would give her character a darker color than that of being simply a saloon hostess.

To prepare for her role in the whip dance, Gray went to a sport shop and bought a bullwhip. Working with it, she discovered, was grueling. The work fueled her anger and frustration when Kidd finally refused to allow her to be part of the number.

Couldn’t she just crack her whip one time? No, he answered. Couldn’t she throw her whip to one of the three henchmen? No. “Michael, this is supposed to be a pivotal character moment for me,” she pleaded. He was unyielding.

As for Merrick, he was never available. Often he would be out of town. He also had several other shows in development, notably Gypsy, which would open six weeks after “Destry.”

By the time “Destry” began its out-of-town tryout in Boston, Gray and Kidd were both at the boiling point. Nor did it help matters that she had virtually no relations with her leading man [Andy Griffith], who was nervous about appearing in a musical.

After one of the performances Kidd and Gray had a heated argument in front of the cast. He called her a “slut.” That word had been in the script. It had made Boston audiences gasp. She asked him to take it out. It had upset her when it was part of the show. It outraged her when Kidd applied it to her. She upped the verbal ante. She slapped him. He slugged her.

It made headlines. A Herald-Tribune reporter flew to Boston to report on the backstage rodeo. After a performance he saw Kidd accosted by Gray’s mother, who slapped him hard across the mouth. A companion dragged her into her daughter’s dressing room, from which she called out, “You haven’t heard the last of this, Michael Kidd. I will kill you, Michael Kidd.”

Normally it would be the producers’ role in such a situation to restore peace and harmony. Merrick, however, refused even to fly to Boston. Gray’s agent, Lester Shurr, pleaded with him, “You promised her a lot of things. The least you can do is go up there and back her up.”

“Are you crazy, Lester?” Merrick told him. “I couldn’t buy publicity like this for $5,000 a week. Let ‘em fight it out.” [close quote]

[Separately, in this staging of a gruesome “hangin'” production number by Kidd, I see vocabulary by Agnes de Mille, Martha Graham and Jack Cole.]

Excerpted from Kissel, Howard, David Merrick: The Abominable Showman, the unauthorized biography (New York, London: Applause), 1993, pp.156-58