[ed. note: author Kirk Silsbee’s story was originally published, in slightly different form, in the L.A.Weekly]

Some people only have one hit record in them. History’s one-hit wonders make up a long, sometimes colorful and often tragic legion. Eden Ahbez was lucky. He had a compelling song, with an unusual melody and a gentle message that struck a universal chord. But having a song was not enough; he had to wangle it to Nat Cole—through his valet, backstage at the Lincoln Theatre on Central Avenue—to get it to the ‘King’. Once he did, Eden Ahbez’s fortunes took a definite upturn.

Underneath the outré name was a garden-variety dance band pianist from Kansas City named George McGrew. Like so many men during the Great Depression, he hopped freight trains. McGrew eventually made it to California in 1939 with the idea of breaking into the Hollywood music business. Though he’d hoboed around the country, California was transformative: George became eden ahbez—affecting the lower case and presaging the North Beach Beats by 15 years at least.

He found a handful of other bohemians who lived off the land and attracted attention for their back-to-nature stance. (Robert Bootzin from San Francisco, the future Topanga Canyon Aquarian who would go by Gypsy Boots and inject good-natured mayhem into The Steve Allen Show, was one of them.) Ahbez slept under the stars—in the desert, under the Hollywood Sign, in Griffith Park and in the backyards of SoCal friends. Except for his later years living out of a van, that was pretty much his pattern for most of the rest of his life. Even when “Nature Boy” was cracking the Hit Parade and LIFE magazine came calling, Ahbez seemed most comfortable away from the spotlight. He knew how to assume the ascetic naturmensch posture and trade off the curious attention that came his way, but Ahbez could also knock on the doors of the Capitol Tower on Vine Street.

In 1948, Nat Cole didn’t just turn “Nature Boy” into a number one hit; he made it a standard. The phenomenal success of the song continues to this day—Sinatra, Doris Day, George Benson, David Bowie and scores of others have all recorded it.

But there was trouble in paradise. Tunesmith Herman Tablokof claimed the melody was nicked from his Yiddish theater song; he was subsequently paid a substantial out-of-court settlement. Cole’s valet, Otis Pollard, had to split his take (one-sixth of the royalties and publishing) as community property with his ex-wife.

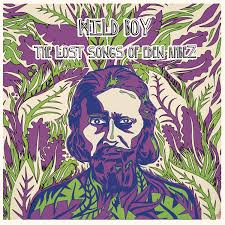

Ahbez, the longhaired, bearded nature boy of the song, wrote many more ditties before he died in 1995 at age 86. Fourteen of them are collected in the new 180-gram 12” vinyl LP (Bear Family).

A hbez scholar Brian Chidester has complied and annotated this clutch, a motley gathering of recorded curios and oddities. Nature Boy piqued the interest of successive generations of Beats, hippies, rockers, New Agers, tiki and exotica aficionados, yet Ahbez was never able to either repeat his hit record breakthrough or become quite the transformative figure that Chidester suggests. Collectors and devotees of California bohemia will likely be the audience for Wild Boy.

hbez scholar Brian Chidester has complied and annotated this clutch, a motley gathering of recorded curios and oddities. Nature Boy piqued the interest of successive generations of Beats, hippies, rockers, New Agers, tiki and exotica aficionados, yet Ahbez was never able to either repeat his hit record breakthrough or become quite the transformative figure that Chidester suggests. Collectors and devotees of California bohemia will likely be the audience for Wild Boy.

The selections range from Nat Cole crooning “Land of Love,” to the moony Talbot Brothers’ English ballad treatment of “Nature Boy,” to trumpeter Ray Anthony’s Vegas-style flag-waver “Palm Springs,” to Eartha Kitt’s breathy vocals and beady vibrato on “Hey Jacque,” to Arthur Lyman’s somnambulant marimba for “Eden’s Island,” to Pat Boone sound-alike John Harris handling “Monterey” and “Overcomers of the World.” The former nods to the Monterey Jazz Festival (“I was up in Monterey, and I heard the hippies play…”) and the latter oozes New Age floss (“…love will make this world so beautiful…”) via Ahbez’s naive lyrics.

After “Nature Boy,” Ahbez seemed to have lost the ability to craft idiosyncratic chord sequences or interesting melodies. Just about all of these selections are two-chord songs, though a few skillful arrangers try to make the most of them. Harry Geller’s charts for “India” and “Child of Nature” (for Ahbez vocals) have all the trimmings of Paul Weston at Capitol Records, including the Randy Van Horne Singers. Cole’s well-chosen piano chords over Geller’s gently swirling strings in “Land of Love” are perhaps the musical high point of this album.

Other studio efforts contain surprises. “Umgowah” (Hollywood B picture vernacular for faux African dialogue) has an early rock and roll beat led by a Dixieland trombone. Mort Wise and the Wisemen’s title track is full of cartoonish jungle noises and leaden percussion before breaking into a rockabilly jag. “Overcomers of the World” might be a recessed civil rights cheer but it’s up to the flute of session man Paul Horn to inject some melodic content. And, yes, that’s a Moog on “The Clam Man,” with its shuffle-off-the-stage vaudeville ending. It’s a bumper car jaunt through an audio funhouse but you probably don’t want to go on that ride too often.

As a singer, Ahbez had about three notes and most of them were flat. It appears, though, that he had tried to market his image for all he was worth through the songs, singing inanities like “I’m an old beach-comber, yes-siree…” and “Don’t forget that clam, be sure and say hello for me.” His melancholy home recording “Anna Was Mine,” for Ahbez’s late wife, is mildly haunting. But “Surfer John” (“John, John, Surfer John was not afraid to die…”) is just good enough for a late night KXLU goof.

Gossip among music industry fringies posits that certain standard tunes were actually written by unacknowledged composers and lyricists. To such self-important insiders-with-a-big-secret, Central Avenue drummer Cee Pee Johnson was the true author of Hoagy Carmichael’s “Stardust,” and marginal tunesmith Shifty Henry gave birth to “Jailhouse Rock” before a delivery room snatch. If they could write those anthems—shouldn’t they have been able to pen follow-ups of equal quality? So where were they?

Though he had a couple of subsequent minor charting songs, Ahbez’s worthy successors to “Nature Boy” never came. Based on the Wild Boy compilation, if he never scored again, it wasn’t from lack of opportunity or from trying.

Sometimes artistic obscurity is justified.

Kirk Silsbee publishes promiscuously on rock, jazz and culture.