Revelations of predatory behavior against women first exposed in the film industry have spread to other corridors of power. The headlines have overshadowed a parallel story involving the shameless disrespect of an iconic figure of Hollywood’s Golden Age. She fought for, and changed, the way the entertainment business is conducted.

That woman, now 101 years old, is Olivia de Havilland, the two-time Oscar-winning Best Actress (The Heiress, To Each His Own) and five-time nominee (Gone With The Wind, The Snake Pit, Hold Back The Dawn). Her most recent distinction was being the eldest person to be named a Dame Commander in Queen Elizabeth’s birthday honors. Beyond these accolades, de Havilland’s perseverance and integrity challenged the severity of the studio contract system—and won.

That woman, now 101 years old, is Olivia de Havilland, the two-time Oscar-winning Best Actress (The Heiress, To Each His Own) and five-time nominee (Gone With The Wind, The Snake Pit, Hold Back The Dawn). Her most recent distinction was being the eldest person to be named a Dame Commander in Queen Elizabeth’s birthday honors. Beyond these accolades, de Havilland’s perseverance and integrity challenged the severity of the studio contract system—and won.

The de Havilland Decision, enacted in 1943, ruled that a personal service contract be limited to seven calendar years and that suspended or inactive work had to be included in that time frame. The studios fought it; the Screen Actors Guild backed it. Johnny Carson eventually invoked it to break his contract with NBC: Jared Leto credits it with resolving his music contract issues.

Now Miss de Havilland, all these years later, is once again in court, in a legal battle, defending her right to be accurately portrayed and consulted in a major production, which according to her, has “falsified her character and demeaned her reputation.” She is suing under the common law right of publicity, statutory right of publicity, unjust enrichment and invasion of privacy. In essence, for putting words in her mouth “which are inaccurate and contrary to the reputation she has built over an 80-year professional life.”

The production in question is FEUD, Ryan Murphy’s ingenious, beautifully filmed series for FX about the legendary rivalry between Bette Davis and Joan Crawford, centered on the development and shooting of Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?, a landmark film that established a new genre for older star actresses.

FEUD’S casting was largely exceptional. Having worked intensely with Bette Davis as the producer of The Whales of August (1987), it was exhilarating to see Susan Sarandon’s perfect channeling of Davis. Jessica Lange and Kathy Bates, respectively, splendidly evoked the driven Joan Crawford and the spunky Joan Blondell.

Among the most unseemly arguments by the FEUD/FX defense team was against accelerating a trial date due to de Havilland’s age. This was disgraceful, thoughtless and cruel; in her 101st year, a delay could have resulted in the actress leaving the planet. The FEUD/FX lawyers lost that argument, along with another that FEUD was exercising its First Amendment rights.

De Havilland’s legal win in 1943 picked up a thread begun by a gutsy Bette Davis in her fight at Warner Bros. for better roles. Davis lost her case, but this sisterly struggle cemented a long friendship, with De Havilland taking up the cause of actor empowerment.

In FEUD, however, that solid friendship goes unexplored. The sole purpose for

de Havilland’s scenes appears to be having a famous name spout Hollywood gossip, notably that Frank Sinatra ‘must have drunk all the liquor backstage at the Oscars as there was none left.’ As played by Catherine Zeta-Jones (above), none of de Havilland’s aura and grace are on view. It rings false, regardless of the accurate recreation of her wardrobe.

Elsewhere in FEUD, de Havilland calls her sister, Joan Fontaine, ‘a bitch,’ compounding the insult to de Havilland’s dignity. Perhaps this was included to shadow the reported tension between the two sisters, but the tone is wrong. One can’t imagine Olivia de Havilland using that invective, even in private. She has always conducted herself with honor, class and steely resolve.

Elsewhere in FEUD, de Havilland calls her sister, Joan Fontaine, ‘a bitch,’ compounding the insult to de Havilland’s dignity. Perhaps this was included to shadow the reported tension between the two sisters, but the tone is wrong. One can’t imagine Olivia de Havilland using that invective, even in private. She has always conducted herself with honor, class and steely resolve.

Olivia de Havilland’s high character was obvious to me in my two encounters with her over the years.

When I was an MGM publicist, she was the focus for the 1967 technically enhanced re-issue of Gone With The Wind. We had several lengthy meetings planning her media activities and her personal requests. She impressed with her courtesy and professionalism.

Shortly after her arrival to New York from Paris, we accidentally met a few blocks from the MGM Building. I knew she had no interviews scheduled so asked if she wanted to join myself and a colleague for lunch. Thanking us for the invitation she declined as she ‘was having lunch with her sister.’ Everyone was aware of their stormy relationship, but her response was matter of fact. No wink, no innuendo of a difficult engagement.

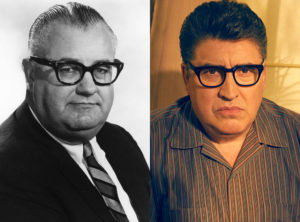

Supporting de Havilland’s case is the similarly egregious depiction of “Baby Jane” director Robert Aldrich, the main male figure in the series. If Aldrich were alive, I’m certain he would have either separately instituted a lawsuit or joined forces with de Havilland for his gross misrepresentation in Alfred Molina’s portrayal of a wimpy, panicky, fearful man.

Actor Michael Murphy (Nashville, Manhattan, An Unmarried Woman), worked with Aldrich on Lylah, and powerfully agrees. Murphy told me in an email, “I gave up on FEUD after watching a few minutes of what they did to Bob Aldrich. Unbelievably insulting and bore not a single resemblance to the real man!”

Actor Michael Murphy (Nashville, Manhattan, An Unmarried Woman), worked with Aldrich on Lylah, and powerfully agrees. Murphy told me in an email, “I gave up on FEUD after watching a few minutes of what they did to Bob Aldrich. Unbelievably insulting and bore not a single resemblance to the real man!”

Like Davis and de Havilland, Aldrich was a fighter, a ballsy iconoclastic figure from a prominent family who tackled tough subjects (Kiss Me Deadly, The Killing of Sister George) as well as adding edge, sometimes fiercely, to conventional genres (Attack, The Dirty Dozen) He understood the harsh workings of the film business, which he dissected in The Big Knife and in his under-rated bitter comedy, The Legend of Lylah Clare. For his unadulterated take on moviemaking, the coda in Lylah Clare says it all. (Warner Bros. studio head Jack Warner would have been the last person he would have asked to assess his talent, as written in a flagrantly fictitious scene.)

When Joan Crawford withdrew from Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte (the even better follow-up to Baby Jane), Bette immediately called her friend in Paris and a script was sent. De Havilland turned it down but Bette insisted that Aldrich could persuade de Havilland in person. Aldrich flew to Paris, made his case, and the deal was done.

One way of avoiding this embarrassing lawsuit—it could be construed as elder harassment—requiring Miss de Havilland to appear in a Los Angeles court, might have been to take a similar personal approach.

Olivia de Havilland is a peripheral figure in FEUD. Her segments could be re-edited without losing any dramatic essentials, saving what will undoubtedly be huge legal costs. Perhaps Ryan Murphy and the Murdoch children could still visit Paris, taking the cue from Davis and Aldrich. For given de Havilland’s determination and her history of fighting for principle, one can expect that should she lose her case, she will appeal.

In 1988, Olivia de Havilland made a special appearance at the Academy Awards. She received a standing ovation,

I was accompanying Ann Sothern, who had been nominated for her performance in WHALES. Ann lost to Olympia Dukakis in the very first category to be announced and was emotionally upset, compounded by her longstanding mobility issues stemming from a stage accident that seriously injured her back.

She had co-starred with de Havilland in LADY IN A CAGE. When de Havilland made her entrance, Ann rose, moving for the first and only time that evening.

She said, “I have to stand for Olivia.”

It’s time for the industry to stand for Olivia.

Like her female contemporaries — Davis, Crawford, Sothern, Barbara Stanwyck, Loretta Young, Maureen O’Hara, Katharine Hepburn – de Havilland learned how to survive and navigate Hollywood’s waters through intelligence, fortitude and self-confidence. She is continuing that struggle.

Being a woman, residing in Paris for decades and carrying a French surname, I don’t think we’d be witnessing this court case if the artist in question were the other remaining centenarian from the “Golden Age” – Kirk Douglas.

She appears to have followed the I-Ching precept: PERSEVERANCE FURTHERS…

It is what we’ve come to expect from Dame Olivia de Havilland.

photo: portrait of de havilland, los angeles times

* * *

Author Mike Kaplan has worked as a producer, distributor, documentary director, marketing strategist, actor, and campaign designer in close association with directors Stanley Kubrick, Robert Altman, Hal Ashby, Lindsay Anderson, Mike Hodges, Barbet Schroeder, Alan Rudolph and Abraham Polonsky. He is author of GOTTA DANCE, The Art of the Dance Movie Poster.

Fascinating. Glad you mentioned Kirk Douglas, who just turned 101.

Having just heard that the newest Churchill movie consulted with Sir Winston’s great great grandson during production, one wonders why FEUD couldn’t have picked up the phone and asked what really happened. No doubt it’s Hollywood’s Carolinian need for everything to be “twice as natural.” But isn’t that Hollywood just serving our id what we ordered?