Hollywood photographers have always had to walk a fine line. Their work is contingent on access to the celebrated, but entree hinges on trust and following implicit rules of privacy. Movie studios have always wanted their actors and directors depicted in the best possible light and they’ve rewarded those whose images flatter most. But good photographers pursue a sort of essence—even in the most controlled settings—that gives a glimpse of what lies beneath the greasepaint. Phil Stern’s work has a backstage intimacy that borders on telling tales out of class.

Hollywood photographers have always had to walk a fine line. Their work is contingent on access to the celebrated, but entree hinges on trust and following implicit rules of privacy. Movie studios have always wanted their actors and directors depicted in the best possible light and they’ve rewarded those whose images flatter most. But good photographers pursue a sort of essence—even in the most controlled settings—that gives a glimpse of what lies beneath the greasepaint. Phil Stern’s work has a backstage intimacy that borders on telling tales out of class.

At 94, Stern is probably the last of the in-crowd Hollywood photographers to utilize the post-World War II candor that would eventually augur the end of the iron-fisted studio system.

Fahey/Klein Gallery, which represents his work, has mounted a show of 27 large-scale Stern prints: “Hollywood Big Shots.” Some of the images have attained iconic status; others may be new to most viewers.

Observing this grouping, we feel like Stern’s silent assistant as he navigates through dressing rooms, soundstages, parties, back lots, recording studios, movie locations, rehearsal halls and orchestra pits.

An automobile mishap in New York City brought Stern and James Dean face to face for the first time. Three well-known Dean photos, including the actor’s attempt to disappear into his sweater, are in the show.

An automobile mishap in New York City brought Stern and James Dean face to face for the first time. Three well-known Dean photos, including the actor’s attempt to disappear into his sweater, are in the show.

Marlon Brando looks every inch the stud as he struts on the set of “The Wild One”; a more reflective Brando sits in a dressing room, a fresh scar on his face. John Wayne, in too-tight and too-short shorts, is every inch the tourista in Acapulco in 1958. Sophia Loren looks peeved and bored out of her mind on a desert location.

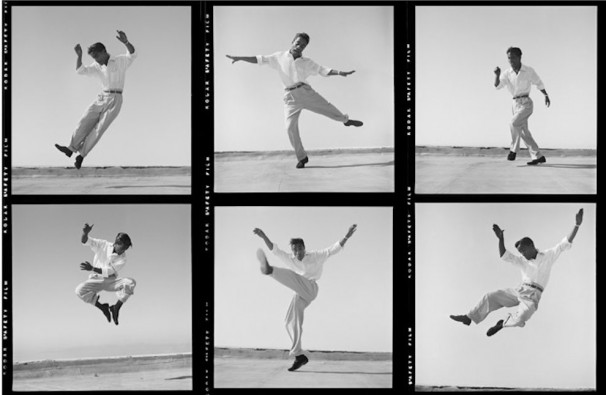

A 1947 contact sheet of young Sammy Davis Jr., jumping and kicking on a rooftop, presaged his emergence as the Michael Jackson of his day. At that juncture in his life, all he had was talent. Ray Charles surges with energy as he idly tries out a battered upright piano in a studio, prior to his “Porgy and Bess” album with Cleo Laine in 1975.

Stardom is a drug, and it’s killed many. The most poignant image in the show is of Marilyn Monroe in 1953, backstage at a show at the Shrine Auditorium. She’s young, she’s beautiful, she’s radiantly gowned, and she’s scared to death. Jack Benny’s wizened visage frames the lower right quadrant of the photo, oblivious to her terror.

Frank Sinatra and his Rat Pack pals are front and center in this exhibition. The onstage antics (Frank carrying a bass drum while Joey Bishop, Dean Martin, Sammy and Peter Lawford stand and salute) is pure star power, albeit in an adolescent mood. Stern caught Sinatra alone in the spotlight, singing at President Kennedy’s Inaugural Ball, and it’s suddenly a new kind of power. A grainy candid catches FS lighting JFK’s cigarette, signaling the beginning of the Hollywood and Washington D.C. pas de deux that continues to this day.

A Rat Pack stage shot shows Frank catting with Shirley MacLaine in the front row. He had all the prerogatives of stardom and he exercised them to the utmost. That contrasts with The Voice, sitting in the middle of a studio orchestra, studying a score, as strings and French horns play their parts. He’s in the eye of the musical storm, yet somehow completely alone. He may have been as unrestrained and undisciplined as a 16-year old with a new Jaguar elsewhere, but Sinatra was all business when it was time to take care of business.

The show is up until February 20. Get a glimpse of what stardom used to look like.

Phil Stern’s Hollywood Big Shots | Fahey/Klein Gallery

Kirk Silsbee publishes promiscuously on jazz and culture.

The “accidental” first meeting between Dean and Stern happened on Sunset Boulevard, not New York as you report. Mr. Stern has told and re-told this fateful encounter many times over the years.