Opera lovers in London have any numbers of possibilities. We can go mammoth: Aida in the Royal Albert Hall for an audience of 3500 with singers and orchestra miked to the max; or miniscule: the prizing-winning Opera Up Close at the Kings Head Theatre Pub in Islington for 110, its Prohibition-set Traviata currently running until the end of the month. During the summer we can listen near al fresco at Opera Holland Park or trek out to Glyndebourne in East Sussex, where Mozart, Wagner, Janacek and Purcell are chased with picnics in formal dress while sheep graze across the ha-ha. If our tastes are for the obscure, there’s the Classical Opera Company. (Mozart’s Apollo et Hyacinthus or Lucio Silla anyone?) But above all these are our two pillars: Covent Garden’s Royal Opera House and English National Opera.

The Royal Opera House is all one expects of grand opera: tall, wide spaces in which to see and be seen; the Queen’s golden initials embellishing the red velvet curtains; the shiniest international stars on stage, with ticket prices to match; and often enough, a very rewarding night out. But for those of us who seek the new, the unusual and sometimes the edgy, English National Opera, under the leadership since 2005 of artistic director John Berry, has become the place to be. Original in its thinking and quick on its feet, ENO has become something of a surrogate mother to the Met in recent years: Andrew Minghella’s Madam Butterfly with puppetry, Philip Glass’ Satyagraha, Peter Sellars’ production of John Adams’ Nixon in China, Nico Mulhy’s Two Boys, and Deborah Warner’s preternaturally beautiful Eugene Onegin. Berry has made a point of encouraging directorial talent from other genres to bring their unique capabilities to opera: in addition to Minghella, film directors Mike Figgis and Terry Gilliam, actress Fiona Shaw and also, with added encouragement of the Netherlands Opera’s Pierre Audi, the visionary founder and Artistic Director of the Complicité theatre company, Simon McBurney.

After a successful first outing based on Bulgakov’s A Dog’s Heart in 2010, McBurney returned to ENO last week with a Magic Flute that is nothing short of revolutionary. The first expectations in regards to Mozart’s last opera: color, lots of it, in the costumes, in the sets, in the birds and monsters. Maybe some puppets. Lots of Masonic flim-flam to get through somehow, loving it or just wading through it.

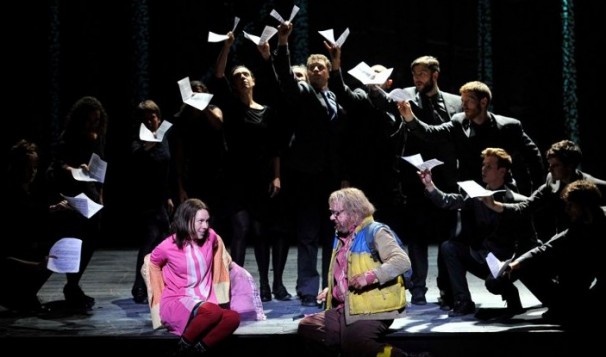

Well, forget it. Save for Papageno’s costume (and later that of his lady love) there’s almost no color at all. The dress is modern and somber. Early on Tamino is stripped of his purple sweat suit to uncover the pristine white tee-shirt more appropriate to a search for love and truth in a post-apocalyptic world. Papageno’s birds are represented, Complicité-style, by actors manipulating pieces of sheet music. The stage is black-planked and bare with a platform that rises, falls, twists, and turns with a glass-paneled foley cabinet on one end and a visual artist’s both on the other where much magic is generated with projected chalk drawings into lighting designed by veteran magician Jean Kalman. Doing what he can to, if not fully remedy, then at least ease the misogynies of The Magic Flute’s libretto, McBurney is concerned with enlightenment (indeed the toddler-stage Enlightenment at the opera’s debut in 1791) the forces that oppose it — not just the mother/harpy Queen of the Night vs Sarastro’s wisdom , but youthful lust vs enlightened love as well – and finally the magical power of music, for in the playing of Tamino’s flute and Papageno’s bells (here pointedly given orchestra members to perform) man, woman and their world are transformed for the good.

Playwright Stephen Jeffries‘s new translation (all ENO operas are presented in English) didn’t always track easily with the music, especially in the first act, but lent a vibrant and often hilarious modernity to a piece that started life as a combination of pantomime, solemn ritual and ribald Viennese humor. Not a show for young children, but so many delights!

photo credit: courtesy English National Opera, Robbie Jack

Candace Allen lives in London. She is the author of ‘Soul Music The Pulse of Race and Music.’