ed. note: artsmeme wishes to especially thank dance writer Susan Reiter for her humanity in contributing this appreciation of the marvelous modern dancer/choreographer Ken Rinker. You may experience a taste of Kenneth in motion in this film’ed excerpt from “The Bix Pieces.”

On a September evening in 1972, I had a dance epiphany that has remained vivid in my memory ever since. I was at the Delacorte Theater in Central Park, experiencing Twyla Tharp’s choreography for the first time. Tharp and her four company members moved in sensuous, intricate ways utterly new to my eye in the New York premiere of The Bix Pieces. The style was sophisticated, inventive, richly layered as well as deeply personal.

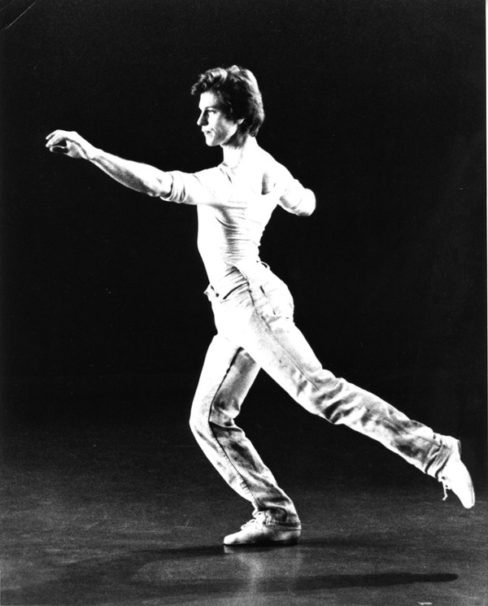

A single male dancer, Kenneth Rinker (1945-2022), added something offbeat and unsettling as he more than held his own amid the sensational women—Tharp, Sara Rudner, Rose Marie Wright and Isabel Garcia-Lorca. He was notable for a quietly focused stage presence, his fluidity, and the way he embodied the sly elegance of the Bix Beiderbecke jazz compositions.

As a company member from 1971 to 1977, Rinker, who died last week, was an integral participant in Tharp’s brilliance and expansive originality. He was in the original casts of Sue’s Leg, Deuce Coupe, Bach Duet and many more works during that pivotal era. It’s been decades since I’d seen him dance, but, learning of his death, the memories flooded back. He was part of my Tharp education.

In her autobiography, Push Comes to Shove, Tharp wrote: “I had been coveting Kenneth Rinker for the company since first seeing him at Merce [Cunningham]’s Studio in 1969. Wonderfully musical, his dancing was unusually fluid for a man, capable of small, precise articulations and possessing an acute rhythmic sophistication. I figured his virtuosity could be quickly absorbed into our company, and after a careful courtship, he said yes.”

A native of Washington, D.C., Rinker discovered modern dance at University of Maryland, and had found his way to New York where he studied with Cunningham whose company he held hopes of joining. But Tharp came calling, soon after she’d created her breakthrough Eight Jelly Rolls and just in time for the new high she reached with Bix Pieces. Their paths crossed just as she was ready to expand the feisty troupe she had once described as “a bunch of broads doing God’s work.”

In her invaluable and penetrating book about Tharp’s body of work, Howling Near Heaven, Marcia B. Siegel quotes Rinker: “I got on the Twyla Tharp train at a time when it was changing from local to express… the wheels turning faster and the train getting grander and the stops being spiffier.”

Siegel writes, “Whenever she was quizzed about accepting Ken Rinker as the first man in her company, [Tharp] replied that she was interested in using whatever skills dancers could add to her work – she’d just been waiting for one who was good enough.”

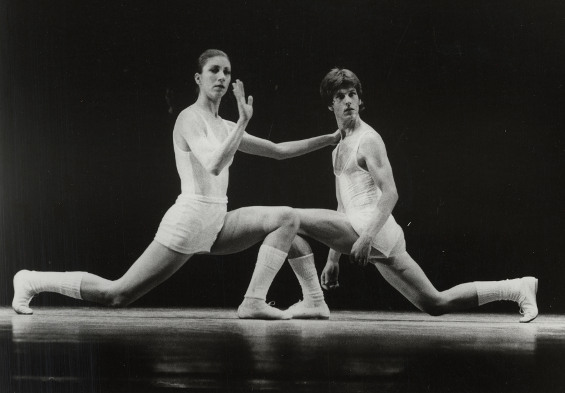

Rinker was often paired with the iconic, ballet-trained Tharpian, Rose Marie Wright. Tharp immediately created a section of Bix Pieces in which they shared the stage. “Wright had enough individuality and Rinker had enough technique that they already embodied the fusion Tharp perfected during the next decade,” Siegel writes. They danced together in Bach Duet, a 1974 piece (yet another Delacorte epiphany for me) that fell out of the repertory after 1980. (Hopefully, given Tharp’s extensive videotaping of all her choreography, it exists somewhere in the archives.)

Rinker rode that Tharp express train with memorable individuality and brilliance through 1977, and he was her assistant when she made her move into the commercial world to choreograph the dance sequences in the film Hair.

He had occasionally created his own dances during his Tharp tenure, and focused more intensely on choreography during the 1980s, presenting his works at Dance Theater Workshop and the Kennedy Center’s Terrace Theater. In a 1981 New York Times review, Anna Kisselgoff wrote, “Mr. Rinker’s own choreographic style, slinky loose-hipped, virtuosic and an elegant distortion of every idiom from ballet to natural-movement-modern bursts out into wide dynamic range.”

Rinker often choreographed to music by his lifelong partner, Sergio Cervetti, whom he met in college. I came across this very personal expansive 2012 interview in which Rinker reflects on their lives, relationship, and connection to the times through which they lived.

Just as Rinker’s performances still resonate nearly five decades later, his impact on Tharp’s work went beyond the 1970s, since he established a template for her company’s male dancers, as she continued to add incredibly skilled and individual men over the years. One who joined soon after Rinker left and put his own memorable stamp on her repertory was Richard Colton, whom Siegel quotes as having his own powerful response to Rinker’s dancing in Bix Pieces: “I don’t think I’d ever seen a male dancer move like that before.”

Susan Reiter covers dance for TDF Stages and contributes regularly to the Los Angeles Times, Playbill, Dance Australia and other publications.

Thank you for this lovely piece about Ken Rinker. I was lucky to see 42nd/42nd Street Variations in 1979 at Dance Theater Workshop and felt it was the best art I’d seen in any medium in NYC since moving home after college. I joined a Rinker dance workshop, stayed as an artist and worked with the company for the next two years as my models. See http://www.paulbgoodevision.com/vision4/valerie_main.html or https://mvhospital.org/art/valerie-sonnenthal/

FYI The 5-panel Ode to Dance are Art Bridgman and Myrna Packer.