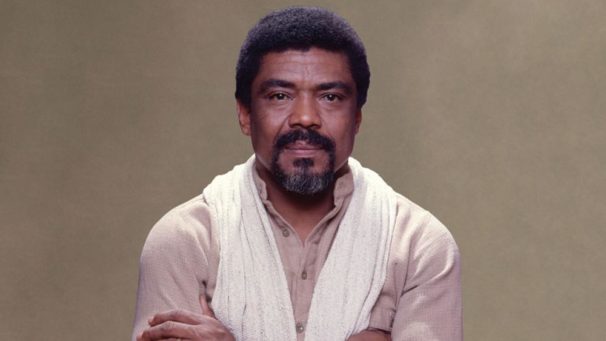

The opening moments of Ailey—Jamila Wignot’s deeply rewarding documentary about Alvin Ailey’s life, work and company—show the choreographer receiving a huge ovation as a Kennedy Center Honoree. Cicely Tyson speaks movingly about the depth of his achievements; his company performs a fervent finale from Revelations as he takes evident pride in watching them. Ailey, 57, looks fit and radiant. It was December 4, 1988.

One year later, on December 1, 1989, he would die, far too young. He would leave a dance company that for more than three decades had only known him as its director.

Ms. Wignot presents a vivid portrayal of both Ailey the man and the arts organization bearing his name that is so renowned worldwide. But before she explores Ailey’s past—his roots in Texas and how deeply they affected his art—she sets up the framing device of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in 2018 during early rehearsals for Rennie Harris’ Lazarus. The company reached its 60th anniversary that year and Harris, arguably the paramount specialist in hip-hop choreography, was commissioned to mark the occasion with a two-act work “that delves into aspects of Alvin Ailey’s life,” as Artistic Director Robert Battle explains.

The scenes of Lazarus rehearsals, interspersed throughout the mostly chronologically organized film, are sometimes jarring interruptions. But they do serve the purpose of establishing the company as a fiercely engaged, contemporary troupe that forges ahead while honoring its roots. And the sight of powerful, distinctive dancers working in the spacious studio that is within Ailey’s own large, bustling building, makes its own statement about the distance this once-fledgling company has come.

Archival interviews with Ailey reveal his eloquence, deep reservoir of memories, and the inner compulsion that led him from an impoverished Texas childhood (no father present; his mother laboring in the fields) to the world’s leading dance stages.

“It was a time of love, a time of caring – a time when people didn’t have much but they had each other,” says Ailey of his past. After viewing archival footage in preparation for Lazarus, Rennie Harris says, “Ailey talked about blood memories, and that was a major key for me. Memory, that was the anchor.”

Those memories include Ailey’s discovery of Katherine Dunham and her company and the impact of seeing black men dance: “The jumps, the agility, the sensuality of what they did blew me away.”

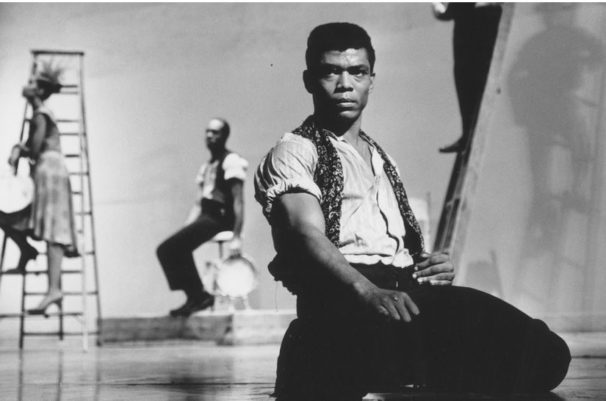

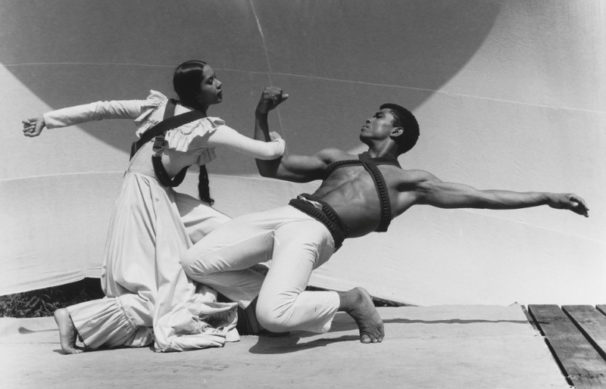

The generous footage of Ailey dancers from multiple generations is riveting, and nothing can equal the sinuous power and athletic grace of Ailey’s own movement. One of the earliest clips shows Ailey and Carmen de Lavallade in a Lester Horton duet. Both are impossibly young and stunningly eloquent movers. Ailey sums up what he learned at Horton’s Melrose Avenue dance studio: “It was a complete education. Lester taught us to justify movement—not just do a step but to feel something about the step.”

The broad array of Ailey colleagues who speak in the film represent the company’s various eras as it evolved and gained in stature. Mary Barnett, Judith Jamison, William Hammond, Sylvia Waters and Masazumi Chaya are among them. Ailey’s early dancers express a deep emotional gratitude for what he gave them. George Faison says, “Alvin entertained my thoughts and dreams that a black boy could actually dance; it was a universe that I could go into, escape to that would allow me to do anything that I wanted.”

The film works its way through exhilaration towards the increasing stresses and burdens that Ailey encountered. “Sometimes your name becomes bigger than yourself,” De Lavallade observes. Bill T. Jones unsparingly points out the burdens and constraints Ailey shouldered as THE black choreographer of American modern dance. The decline of Ailey’s health, both physical and mental, is painfully recounted.

The dance-geeky among us always want dates and dancer identification in historic footage culled from TV programs as well as filmed performances. (I longed to know who the three men were in a particularly vivid “Sinner Man,” and who danced the central role in footage of Memoria.) The film is airing on PBS American Masters (and on its website) after screenings at the 2021 Sundance and Tribeca film festivals and having a brief theatrical run. So it’s aimed at reaching as broad an audience as possible, allowing insight into this singularly original and potent force in American dance.

Susan Reiter covers dance for TDF Stages and contributes regularly to the Los Angeles Times, Playbill, Dance Australia and other publications.