Excerpted from “Maria Tallchief, America’s Ballerina, Larry Kaplan [University of Florida: 2005]:

When I was twelve years old and Marjorie was ten and a half, we went to a new ballet teacher. A ballet mother at Mr. Belcher’s told Mother that the great Bronislava Nijinska had opened a studio near Beverly Hills, and even though I’m not sure Mother knew who Nijinska was, she decided to have Marjorie and me study with her. Without telling Mr. Belcher, she enrolled us at her school.

The new studio seemed no different from Mr. Belcher’s. Little girls were changing into leotards, and mothers were milling about gossiping. A small, rotund gray-haired woman with great, big, luminous green eyes was counting heads. I thought she was the secretary.

When the pianist entered and bowed to her, the little gray-haired woman clapped her hands, a signal for students to take their places at the barre. In a flash, I realized who she was. By then, there was no mistaking Madame Nijinska. Everyone at the school was in awe of her.

Bronislava Nijinska was the sister of the fabulous Vaslav Nijinsky, and like him a graduate of the Imperial Theatre School in St. Petersburg, Russia. She too had danced at the Maryinsky Theatre and with Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in Europe, and she was also a choreographer. Two of her ballets, Les Noces and Les Biches, were classics.

When we started working I saw at once that Madame’s class was rigorous. Students weren’t allowed to slouch at the barre or hang on it haphazardly, and we had to be conscious of each exercise. After we finished doing a step, we had to walk to the side and stand still with perfect posture until it was time to take our places for the next exercise. At the same time, Madame indicated that we should watch our fellow students closely and listen to every correction.

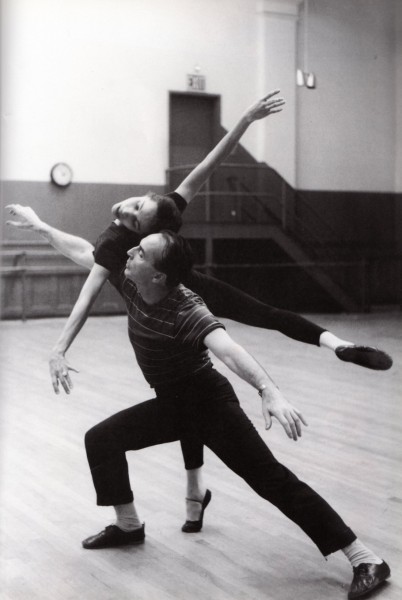

Because her English was practically nonexistent Madame Nijinska rarely spoke. She didn’t have to. She had incredible personal magnetism and she radiated authority. Most of the time she demonstrated. It was hard to imagine her as a ballerina, but how she moved! Her footwork was phenomenal. She jumped and flashed around the studio. I was under her spell. The likes of Madame Nijinska were something I had never seen before.

Every day she dressed in the same pants and plain top; her ballet slippers had a slight heel. In her pointe class, we’d have to repeat steps over and over, learning how to balance and how to hold a position so that our entire backs were being utilized. She was very precise. In first position, elbows had to be held a certain way and the little finger had to touch the front of the thigh. If Madame could come by and move someone’s elbow, the position was wrong.

She was insistent on port de bras, and she told us the reason her brother could jump so high and hover in the air so long was because of the control he had over his abdominals. It was from Madame Nijinska that I first understood that the dancer’s soul is in the middle of the body and that proper breathing is essential.

Even though she wasn’t verbal, Nijinska knew how to get her point across. She communicated with a firm tap on the shoulder. Her husband, Nicholas Singaevsky, sometimes translated, but his English wasn’t much better than hers.

“Madame say you look like spaghetti,” he’d explain, and the message was understood. He’d also expound her philosophy. “Madame say when you sleep, sleep like ballerina. Even on street waiting for bus, stand like ballerina.”

So we didn’t concentrate only for an hour and a half a day on what was being taught. We lived it, and I was beginning to understand just how hard I was going to have to work if I wanted to be a dancer. I was small-hipped and had to work hard for the turnout essential to ballet. But since I was eager to develop, when I was in Nijinska’s class I never took my eyes off her, never looked away, even when she was helping another girl.

The force of Madame Nijinska’s personality, and her unwavering devotion to her art, helped me to understand that ballet was what I wanted to do with my life. In her studio I became committed to becoming a ballerina, and Madame understood I was serious. She saw that I was very musical and had good proportions, and she paid a great deal of attention to me. She was always giving me corrections, a sign of her interest, and little by little she began treating me like her protegee.

In all, I think the importance of the five years of training I had with her can never be overestimated. I was in the right place at the right time. Before Nijinska, I liked ballet but believed that I was destined to become a concert pianist; at age twelve I had given a recital in which I played selections by Bach and Mozart on piano in the first half and danced during the second. Now my goal was different. Two strong women, my mother and my teacher, were directing my destiny, and I loved them both.