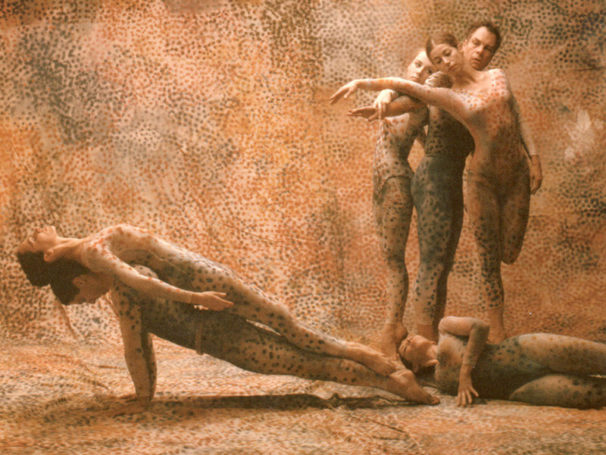

Seen yesterday in Cunningham, the new Merce Cunningham documentary shot in 3-D by writer/director Alla Kovgan: imagery and brief excepts from “Summerspace,” the choreographer’s legendary ‘no-center’ ballet dating from 1958 and performed in Robert Rauschenberg’s pointillist costumes/decor to music by Morton Feldman.

The film, which may bring the rarefied artist his most widespread exposure with a mass audience, gets theatrical release on December 13. It goes far to satisfy the curiosity of people wondering, “What the heck did I miss?”

Prominent in the film, and in the photo above, is the voluptuous figure of the great Cunningham dancer Viola Farber (1931- 1998); one of the doc’s many pleasures is seeing at close range the resilient first-generation Cunningham dancers, a massively idiosyncratic bunch taken one by one. Would that we could steal even more time watching Carolyn Brown, Barbara Lloyd, Valda Setterfield, Gus Solomons, Jr., Sandra Neels, et al in action. (Where was my teacher Albert Reid?) I am proud to have studied extensively with Viola (everyone called her that, so there is no disrespect), as well Sandra Neels and Gus Solomons Jr, featured in the movie.

I also ‘took class’ directly with Merce Cunningham himself, an honor shared by perhaps thousands of my generation of modern dancers, as this generous man gave so much to the art form … touring all over the country, indeed the world, sharing his groundbreaking, collaborative works. Where he went, he gave workshops and master classes. Who even does that anymore?

The film, which proceeds chronologically, is chock-filled with gorgeous re-stagings of seminal works in splendid mise-en-scenes (one in a forest glen, another in an airport terminal, also used: the Westbeth rooftop). It spans the first swathe of Cunningham’s (post-Martha Graham) career, leaving off circa 1970 — rather abruptly, thus begging a second chapter. It also reveals, as much as possible, this hybrid faun-man — a role model of strangeness — as an exceptionally kind and caring human being. His life was a surrogate for ‘devoted artist,’ as well as, in his first years as a choreographer, a ‘starving’ one. Heard in the film in his own voice, Merce crystallizes his nearly unwavering, and monastic, view of dance and dancers. This will be revelatory for non dancers to ponder.

Having griped for the last umpteen years about the cruddy clothes dancers wear on stage, I take delight in Cunningham’s cast of unitard-clad dancers. Gorgeous! Vibrant color! And tidy hair: reference Sandra Neels’ little braided pigtails secured by barrettes. Chignons and buns. But if you want to go up-close and personal, meet Merce Cunningham’s spongy bare feet and toes. In this film you will.

Perched in yellow chairs at a press screening was a lineup of Los Angeles-based Cunningham alumni posing in keen anticipation of the film. In the photo: Kerry Stichweh, who understudied with the company, and Holley Farmer, Jeff Slayton, and Kristy Santimyer-Melita who danced in it. All were excited, as they should be, to see this documented slice of dance history, which, if removed, would leave … Well, it’s simply unimaginable to extricate Merce Cunningham from American dance, so weighty, pervasive and enduring is his influence.

Very much absent, however, in Cunningham: the voice of the dance critics who triangulated between a highly enigmatic artist and his adventurous audience. In that nexus took place, over many years, a vibrant cultural conversation. This oversight I would call shameful, but no one cares what critics think.

Cunningham compares to Wim Wenders’ Pina in the wonder of watching glorious dance in 3-D. But for me, it’s so personal. Therefore I call it unmissable.

Dance critic Debra Levine is editor/publisher of arts•meme, the fine-arts blog she founded in 2008.