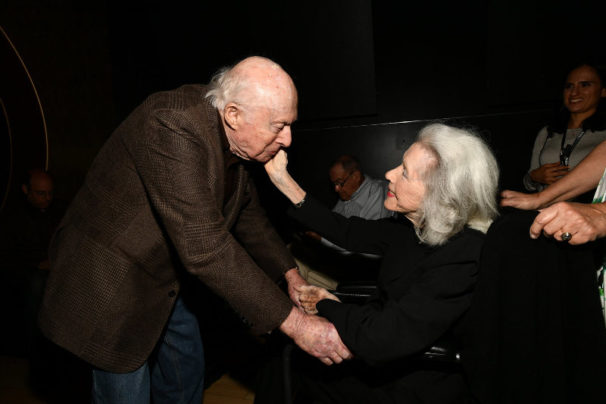

In the year of #MeToo, it seems only appropriate that some of the most resonant films shown at the TCM Classic Film Festival had strong women front and center. Both onscreen and off, 100-year-old Marsha Hunt has long been an inspiring figure. Known for her principled stand against the Hollywood blacklist, which  damaged her career, Hunt has also been honored recently for some of her undiscovered films of the 1940s. One of the most fascinating of these, None Shall Escape from 1944, was one of the true discoveries of this year’s festival. In an interview before the film, Hunt praised the importance of the film, one of the first to acknowledge Nazi war crimes before the end of World War II. She also tickled the audience when she admitted her attraction to roguish émigré director Andre De Toth, whom she called “irresistible.”

damaged her career, Hunt has also been honored recently for some of her undiscovered films of the 1940s. One of the most fascinating of these, None Shall Escape from 1944, was one of the true discoveries of this year’s festival. In an interview before the film, Hunt praised the importance of the film, one of the first to acknowledge Nazi war crimes before the end of World War II. She also tickled the audience when she admitted her attraction to roguish émigré director Andre De Toth, whom she called “irresistible.”

This remarkably prophetic film was made while the War was still raging, but it imagined a war crimes trial that would be convened after the end of the War (anticipating Nuremberg). It focuses on the trial of a high ranking Nazi official in Poland (effectively played by Alexander Knox, who earned an Oscar nomination the same year for his portrayal of the far nobler Woodrow Wilson). Hunt plays a woman who was briefly engaged to him, but she testifies against him at his trial, and flashbacks fill in his nefarious background. When she first knew him in the years after the First World War, his character was a teacher, but as she became more uncomfortable with his fascistic views, she broke off their engagement. She also observed his crimes against Jews and others in Poland as the Nazis rose to power and eventually conquered the country. Hunt is aged for the trial scenes, but she is especially luminous in the flashback scenes. In both sections of the film she conveys intelligence and integrity as she etches a strong-willed character of moral fortitude, not so different from Hunt’s real-life persona.

Another discovery of the festival was one of Ida Lupino’s groundbreaking directorial efforts, Outrage, from 1950. Lupino’s discovery Mala Powers plays a young, smalltown woman who is sexually harassed and then raped by a bully in her town. At that time the Production Code forbade the word “rape,” so the attack against her character is described as a “criminal assault,” but it is quite clear what happened. She is ashamed and devastated, and she feels unable to continue living in the town. So she flees to California, where she gets a job working on a farm. She tries to establish a new identity, but when she attacks another man who makes unwanted advances, her past is finally revealed. Things are wrapped up when we learn that her rapist was finally apprehended for another crime, but the film does not suggest an easy recovery for Powers’ character. The picture, which was co-written as well as directed by Lupino, offers a perceptive dissection of the crippling psychological aftermath of this kind of sexual assault.

Clearly this theme was unusual for a film made in 1950, and it certainly benefited from a woman director’s perspective. Since Lupino was one of the very few female directors working during that period, we can only speculate on the stories that went unexplored because of Hollywood sexism. The film seems especially explosive in the post-Harvey Weinstein era, and although it didn’t draw the same large audience as other films shown at the TCM Festival, it confirmed the value of the festival in showcasing true rediscoveries in addition to high-profile, star-driven events.

One of those higher-profile films this year also had a strong feminist theme, which looms even larger in retrospect. Places in the Heart won Sally Field her second Oscar in 1984 and also earned best original screenplay honors for writer-director Robert Benton. At the festival screening, Field spoke about the luxury of rehearsing with the entire cast, an exceptional ensemble that also included John Malkovich, Danny Glover, Lindsay Crouse, Ed Harris, and Amy Madigan. The meticulous period drama set in Texas in the 1930s centers on the struggles that afflict Field’s character after her husband is accidentally killed. She is suddenly faced with the possibility of eviction from her home unless she can turn her farm into a working cotton producer. Her refusal to accept defeat turns her into a refreshingly strong-willed heroine, and her achievements appear even more significant when viewed through a contemporary lens.

There are other elements in this movie that speak more eloquently to contemporary audiences than they probably did in 1984. The racial prejudice that was so routine in the South throughout much of American history is another potent element in this film, with Glover’s character forced out of town by the Ku Klux Klan in one chilling scene that anticipates last year’s Oscar-nominated Mudbound. The audience at TCM was deeply moved by the film’s memorable finale, which takes a leap into the supernatural with a scene at a church communion that imagines racial reconciliation that this country is still struggling to achieve.

photo credit: TURNER

Stephen Farber, president of the Los Angeles Film Critics Association from 2012-2016, is a frequent contributor to The Hollywood Reporter and Los Angeles Times. He is the author of four books on Hollywood history. He is host of Reel Talk, presented with Landmark Theatres, and Anniversary Classics, presented with Laemmle.