|

|

All elements converged for John Neumeier’s “Liliom,” a two-act narrative ballet presented Saturday night by the choreographer’s stellar company of 38 years, The Hamburg Ballet. The revisiting of Hungarian playwright Ferenc Molnar’s play, adopted by Rodgers & Hammerstein as “Carousel” in 1945, packed much visceral pleasure and emotional punch into one evening at Segerstrom Hall.

Michel Legrand‘s original score—by turns jazzy, then full-blown orchestral— was delivered by a compact, on-stage band of musicians with the composer, a legend, seated in the house. Production designer Ferdinand Wögerbauer provided the tasty scenic tableaux. Neumeier’s advanced skills in translating into dance language almost any human relationship — not just duets but complicated clusters of people — knitted the dance-drama together.

But trumping it all was the vision a great ballerina, Alina Cojocaru, who led the cast as “Julie,” stretching her exquisite arabesque position — pictured above.

A finely rendered, museum-worthy shape, pliant yet sculptural, Cojocaru’s arabesque came at the audience in numerous modes and contexts: often she wrapped it, achingly, around the torso of her partner, Carsten Jung, who played bad-boy Liliom. But she also used it on its own to punctuate space, in a physical expression of defiance, longing, questing, or tenderness.

Having tracked prior Hamburg Ballet spectacles presented in Orange County (where Neumeier is a top favorite of dance curator, Judy Morr, executive vice president of Segerstrom Center for the Arts) from “Lady of the Camellias” to last season’s “The Little Mermaid” (which left me under water), the choreographer/director’s latest, “Liliom,” hit my sweet spot.

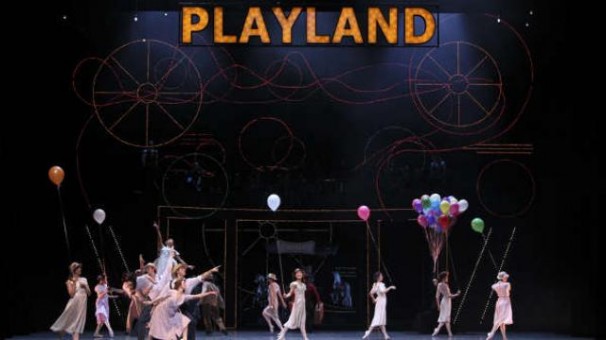

The tale of a tragic recycling of one family’s painful existence (thus the “carousel” metaphor, as it goes ’round), “Liliom” employs a Depression-era carnival for its mise-en-scene; indeed, the first act of the ballet, a colorful promenade of strollers, gawkers and carnie regulars, takes place beneath a dilapidated, lopsided sign for “Playland.”

But the ballet allows its characters no such escape. Julie, as danced by Cojocaru (recently retired after a long career with the Royal Ballet), is hapless in fending off, first, her innocent curiosity and then her animal attraction for the sexual and dangerous Lilom. So onto his treacherous carousel she hops.

I loved the ballet’s sweet park benches used for romancing, while multicolored balloons bobbled above, a simple and symbolic prop. I loved the visit to an employment agency with men milling about gripping “will work” signs. I loved the crazy groupings—a duet for a bell-hop and his sweetheart, and a few complex foursomes requiring high choreographic skill, one of them included luggage — a fine dance maker’s whimsy. Lightbulbs — more “Liliom”‘s props — strung on high evoked a starry night; one such “star” got plucked to earth as a sign of hope. A mime-ish clown, garbed in a long overcoat and so tall he seemed to be on stilts (but he wasn’t), silently traversed the stage dispensing balloons and a sense of doom.

I wept at the male pas de deux that closed the ballet, not the erogenous variety of recent years, but a dance between a ghostly father trying to guide a son he has not raised.

I wept at the male pas de deux that closed the ballet, not the erogenous variety of recent years, but a dance between a ghostly father trying to guide a son he has not raised.

Still, I had quibbles with the evening: I don’t care for “riger mortus” pas de deuxs, and the unfortunate sight of Cojocaru flopping around with Jung’s “dead” body went on too long. A pack of red devils from purgatory, all men, did not work. I wonder if Neumeier couldn’t loosen the reins a bit and allow his production more dance rapture; it’s all so highly controlled, with the choreographer omnipresent. I would have liked to have seen another lead dancer than Jung, whose muscle-bound torso was over displayed.

Other than these minor concerns, “Liliom” proved a wonderful, original narrative ballet forging a brand of neo-romanticism I find appealing. It’s what, in my opinion, classical ballet should be doing more of: using the art form’s technical advancements of the past thirty years but for a purpose: to connect with audiences through ideas, tales and myths, to bring to the stage and to the audience all of the humanity dance has to offer, telling stories, touching lives.