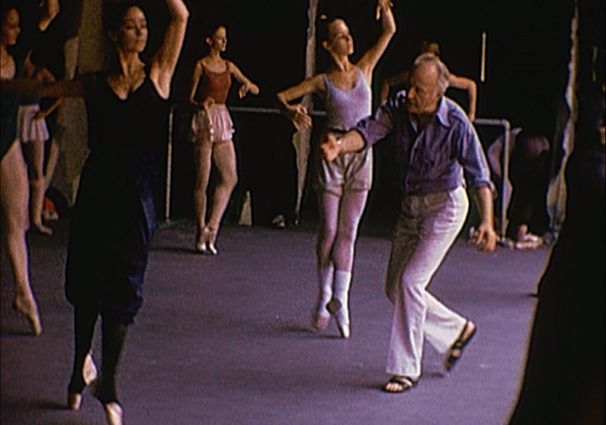

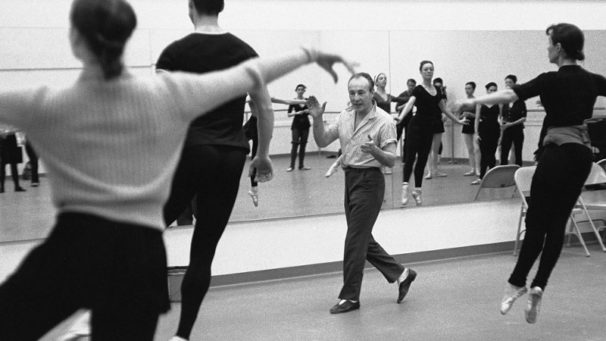

Watching In Balanchine’s Classroom, the new dance documentary directed by Connie Hochman, you wait and hope for a movie about a significant, if rarefied, subject to add up to more than the sum of its parts. But while it includes an abundance of fascinating archival photos and filmed excerpts of George Balanchine teaching and rehearsing his dancers—including famed and revered members of New York City Ballet—it often gives the briefest glimpse before moving on to something else. The 88-minute film never fully comes into focus.

The film’s various tangents have to do with the man himself, the company he founded and nurtured, and several leading dancers who he led to artistry if not glory. But ultimately it lacks a through line and remains a series of moments and impressions.

One must admire the wealth of rare archival material In Balanchine’s Classroom brings together. The opportunity to watch this genius choreographer actively coaching and guiding dancers in some of his seminal works is wonderful, even if the selection and ordering of the footage feels random and scattershot.

Most of it goes undated. Very early in the film an extensive clip is identified as Balanchine teaching company class in 1974. (He’s often heard saying “No.”) After that, we’re left to surmise, or calculate, the time frame of what we’re seeing. One of my favorite moments is a stage rehearsal with Balanchine very animatedly leading the dancers of the “Royal Navy” section of Union Jack, so the time frame for that is pretty clear; it would be circa spring 1976, on the occasion of the U.S. Bicentennial, when City Ballet premiered Mr. B’s homage to the nation’s British roots. Montages and extended series of photos strung together become puzzles to be solved. If one recognizes a certain dancer, one can roughly guesstimate. But only dance geeks of a certain age can do the i.d.s and the math.

Providing at least some connective thread are interviews with several former leading NYCB dancers who speak about their experiences with Balanchine: how he taught and critiqued them and led them to achieve – each at his/her own pace – their full potential. Chief among them is Merrill Ashley, who speaks with analytical clarity and obvious deep appreciation for the patient, in-depth process by which Balanchine nurtured her talent. Heather Watts, chronicling her ups and downs as a more rebellious member of a company of highly disciplined dancers, eloquently reveals her insight and growth. Gloria Govrin, Jacques D’Amboise and Edward Villella provide the perspective from the earlier, formative years as the company grew into one of the world’s most glorious and highly regarded cultural institutions.

Oddly, none of these ballet stars is identified by their title and tenure as NYCB company members. The filmmakers seem to take it for granted that the audience will have that information. The focus is mainly on their work in passing on the Balanchine legacy. The film returns periodically to a very intense rehearsal of Ashley staging Symphony in C for American Ballet Theatre. She’s insightful, yet demanding, as she helps the women navigate technical challenges she knows all too well. Heather Watts is also seen coaching a big star of today, Tiler Peck, in several Balanchine solos; she works, as well, with Unity Phelan and Calvin Royal III on Agon. There are multiple scenes of Edward Villella in class and rehearsal with Miami City Ballet, so his footage was clearly filmed prior to 2012 when he left his position as its artistic director. None of this chronology comes courtesy of In Balanchine’s Classroom.

Other voices are heard as well, however briefly. Suki Schorer’s astute insights and footage of her galvanizing her School of American Ballet students, are terrific. Major dancers of singular significance appear in the parade of photos and filmed moments, but go unidentified. We see Violette Verdy performing an excerpt from her Emeralds solo, Arthur Mitchell and Diana Adams in Agon, and several fleeting but mesmerizing moments of Balanchine coaching Karin von Aroldingen and Peter Martins in Apollo – without ever seeing or hearing their names.

The film’s title leads one to expect a detailed portrait and analysis of Balanchine as teacher, but that is only a portion of what Hochman has assembled. Yes, we do get some valuable insight about how his classes demanded a brave new technique that erased what ballet had been and represented prior to his presence in New York. “I wanted to have a certain way of dancing; I wanted to have clean dancers. So I pushed everybody,” says Balanchine in the film, and each of his students shares their view of what made his classes so unique and forward-looking.

But the film remains a collection of moments, and the overall impression is wafty and unfocused. For this viewer, the film is nearly done-in by the constant, insistent musical wallpaper that accompanies the archival material, even underscoring voice-overs. It’s simple-minded and downright annoying – not to mention an insult to choreography which was created as a brilliant, original response to a specific score. Once in a while – a clip of Tarantella, for example – is shown with its actual music being heard. But this happens all too rarely.

Susan Reiter covers dance for TDF Stages and contributes regularly to the Los Angeles Times, Playbill, Dance Australia and other publications.

In Balanchine’s Classroom | New York Sept 17, Los Angeles Sept 24