courtesy of jeff gold

These days, every self-respecting college and civic performing arts center has a subscription jazz series. It’s no surprise, then, that many people see jazz as concert music. But it wasn’t always so. 1930s and ‘40s jazz musicians mostly worked in ballrooms with dance bands, but they stretched out and jammed in nightclubs and after-hours spots. As the big bands died, clubs became more important to the music. Modern jazz was incubated in ‘40s hothouses like Minton’s and Monroe’s in Harlem. There had been big rooms like the Cotton Club and little cabarets that featured jazz, but jazz clubs were born in the ‘40s.

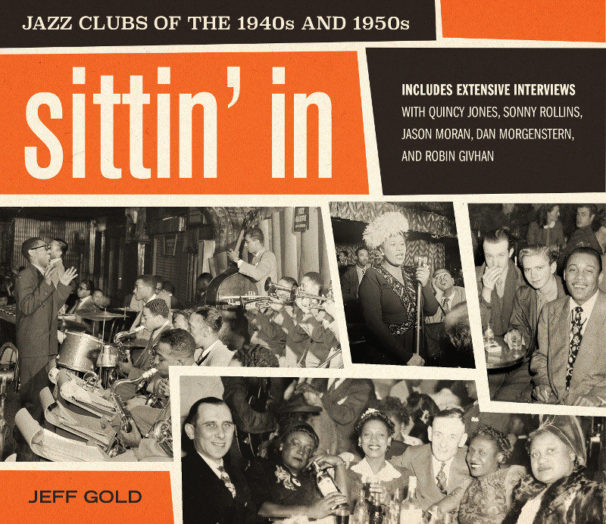

Jeff Gold’s new book, Sittin’ In: Jazz Clubs of the 1940s and 1950s (Harper Design) is a 256-page valentine to the era when the music lived in those spaces. A former Warner Bros. and A&M executive, Gold is recognized as an author (The Story of The Stooges and 101 Essential Rock Records). Gold’s current bread-and-butter is as a rock memorabilia broker with an international clientele.

It was the golden age of American nightclubs, and most of the images of them in Gold’s book are one-of-a-kind, never-published snapshots. On-site shutterbugs prowled those rooms, offering photographic souvenirs of the evening to the swells and their dates. For a price, a “camera girl” snapped a photo of your table, and either developed it on the premises or mailed out the following week.

Gold divides his chapters geographically and New York City gets the lion’s share of space. There’s Charlie Parker, resplendent in a double-breasted pin-stripe suit, smiling next to a young couple at the Royal Roost—the ‘Metropolitan Bopera House.’ There’s Art Blakey, when he drummed for the Billy Eckstine Orchestra, with a couple of fans at the Club Sudan. There’s a gracious Duke Ellington, hob-nobbing with a master sergeant and his girlfriend, at The 400 room. There’s Count Basie with some high-rollers, and Marlon Brando—separately at Birdand. There’s a solitary Billie Holiday at Bop City. There’s harpist Dorothy Ashby at the Garfield Hotel lounge, and singer Tina Dixon at the Flame Show Bar—both in Detroit. And Louis Armstrong and his vocalist, Velma Middleton, with a large party at Chicago’s Deluxe Club.

Gold’s recordmecca.com is an online marketplace of posters, recordings, photographs, tour jackets touching on rock, pop, blues and jazz. “Sittin’ In …” came out of his trade.

Gold was looking over boxes of photographs from a seller when he came upon a few nightclub photos, framed in cardboard folders with the name of the clubs where they were snapped. “I’d never seen one of those from a jazz club,” he says. At his home in Venice, Gold elaborates: “When I took a special interest in them, the guy said, ‘Come down to my bank; let’s look at my safe deposit boxes.’ I sifted through five or six boxes in two or three days, and came up with a hundred and fifty or so of these club photographs. I researched, and I couldn’t find any books on jazz clubs per se. Gradually it came to me that I owed it to history to publish these pictures.”

The club photos are supplemented by better-known images from the big collections, period advertisements and menus. Interviews with musicians Quincy Jones, Sonny Rollins, Jason Moran, jazz scholar Dan Morgenstern and fashion historian Robin Givhan flesh out the folkways and peculiarities of the era. “Not to get morose,” Gold says, “but Quincy, Sonny and Dan are just about the last people who experienced those places.”

courtesy of jeff gold

Jones and Rollins point to the clubs as being in the integration vanguard. Gold says, “Quincy said that jazz musicians never get credit for breaking down racial barriers. Dan started sneaking into 52nd Street clubs at 17; he said the only thing that mattered on those bandstands was whether or not you could play.”

As exhilarating as it is to discover previously unknown images of the jazz stars, the real stars of the book are the audience members. Regardless of where the picture was taken or the ethnicity of the people, they are dressed to the nines. Couples cuddle around circular tables no bigger around than a steering wheel, happy to have a night out on the town with their honeys. “Most of the time the photos we’ve seen these clubs are of the bandstands,’ Gold says. “In my book, we see the interiors and the people who were there. In every shot, they’re having a great time.”

Kirk Silsbee publishes promiscuously on jazz and culture.

Sittin’ In: Jazz Clubs of the 1940s and 1950s | now from Harper Design

My godfather, Herb Rose owned the 331 Cub on West 8th Street in LA. My dad, Frank Klaus was the bouncer, and throughout his life would regal me with stories of hearing the King Cole Trio there. (This was before Nat even began to sing!)

He also loved to tell of the Los Angeles blackout that resulted from Pearl Harbor. Since the club was required to shut down early to avoid possible Japanese attack, they would travel to Watts to listen to music in each other’s homes. And how one night Billie Holiday walked through the door (and sang)!

I’m going to buy this book as a holiday gift for my musician husband. (So I can read it.)