There were other female jazz pianists who also sang in the 1950s, but none shared Jeri Southern’s formidable pianistic technique, vocal individuality, and unerring choice of good material. She sang the most bittersweet love songs in the most intimate manner. And few could inspire the nightclub reveries Southern conjured—of melancholy, infatuation, optimism, idolatry, disconsolation, and lust. She did it all with a cool, unperturbed manner that intimated much while divulging little—a neat trick.

Southern’s peers were Peggy Lee, Julie London, June Christy and Lucy Reed; her admirers included Frank Sinatra, Nat Cole, Ella Fitzgerald and Nina Simone. Jeri wasn’t a retooled big band chirp, a big-finish show singer, a hip jazz chick, a dissolute torcher or a vibratoed cabaret belter. She sang songs about adult situations (like “You Better Go Now” and “Occasional Man”) and she did it in a world-wise manner that implied that whatever the predicament, big girls don’t cry.

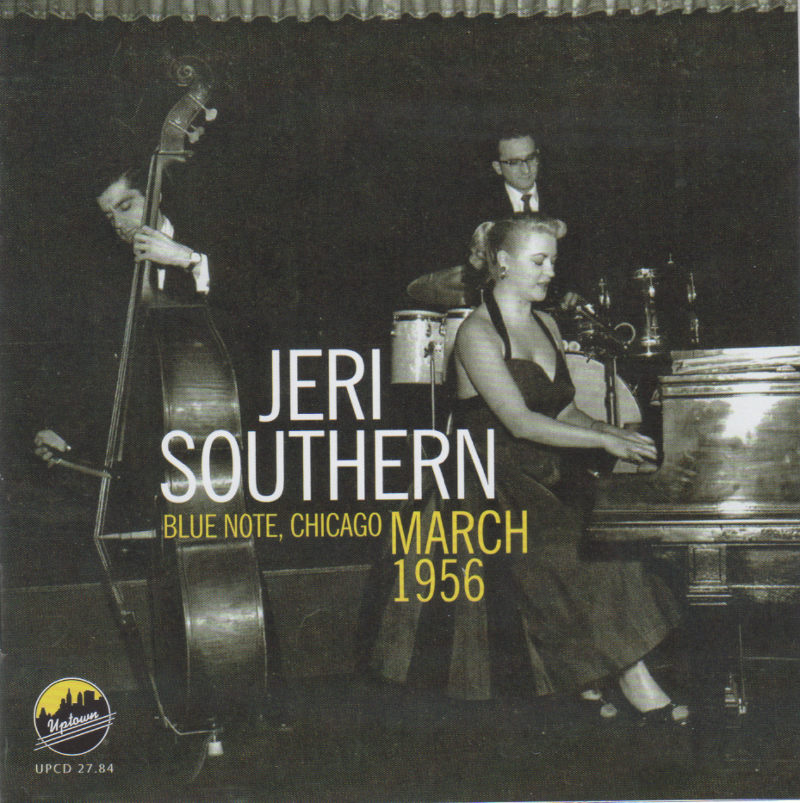

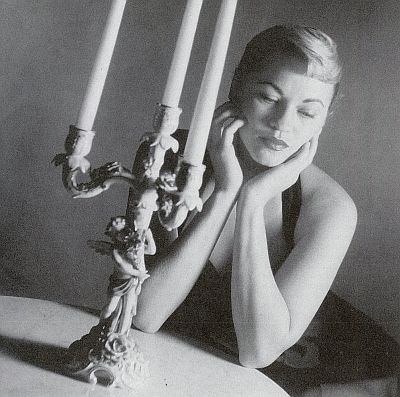

She cut quite a figure onstage, with her bare-shoulder prom gowns, peaches-and-cream complexion and ever-present décolletage. To say that men were smitten is an understatement; she turned them into schoolboys and baying wolves.

Her playing was assured, well studied and full of improvised fillips. She knew all the changes of the songs as they were written and she knew all the hip substitutions. With 15 years of classical training, her playing was hardwired into her singing.

Then there was the voice: a smoky alto, almost spoken rather than sung, and void of affectation or frills. It was a vessel of intimacy, yet Southern herself was elusive: so deferential to the design and intent of a song, she could disappear into it.

Postwar supper clubs, where dinner, drinks and the best musical entertainment were available to the smart set in the 1950s — that was Jeri Southern’s turf.

Although a thorough professional when it came to music, Southern didn’t like show business. Scheduled to guest on a New York radio show to promote an appearance, she was annoyed by the fast-talking announcer. Before the interview began, she excused herself to go the women’s room. Jeri coolly walked out of the building and kept going.

Her career was little more than a decade. Then in 1961, she abruptly stopped performing. She stayed away for 30 years until her passing in 1991.

There aren’t many left who actually saw her work, but anyone truly invested in the great singers and the Great American Songbook should know Jeri Southern’s recordings; her Cole Porter collection on Capitol is one of the great vocal albums of all time. But like Buddy Stewart, Lucy Reed, Blossom Dearie, Jackie Paris, Ernestine Anderson, Beverly Kenney, Shirley Horn, Johnny Hartman, Teri Thornton, Irene Kral and a few others, Southern was a singer’s singer.

She was a Nebraska girl from the tiny town of Royal. The youngest of six, Genevieve Hering’s parents recognized her piano talent and sent her to school in Omaha. She studied classical piano and operatic singing and graduated from Notre Dame Academy. Soon she was playing in hotel lounges and bars.

She moved to Chicago in 1948 and worked as an intermission pianist. Club owners had been after her to sing for some time but it took her first manager, Dick La Palm, to finally convince her. Trained as an operatic soprano, she dialed it all down to a low dynamic. It was La Palm who took note of a nearby bottle of Southern Comfort in a nightclub and came up with her stage moniker.

Peggy Lee brought Jeri to the attention of Decca Records and she had some successes, most notably a remake of “You Better Go Now” and “Dancing on The Ceiling.” Soon La Palm was booking her in New York City, Las Vegas and Hollywood.

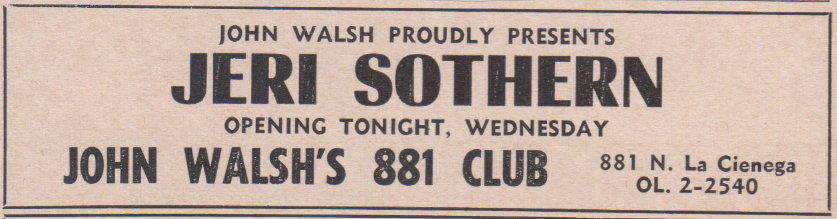

She moved to Los Angeles in about 1952 and it was a plentiful pasture. L.A. was flush with clubs and lounges: the Encore, the Talley-Ho, the 881, the Dover House, the Keynoter and the Avant Garde in West Hollywood, the Haig on Wilshire and the Tiffany on 8th Street in L.A. proper, the Celebrity Room in Studio City, the Keyboard, the Castle and Ye Little Club in Beverly Hills, and the old school big rooms: the Cocoanut Grove, Ciro’s, the Mocambo, the Trocadero and the Crescendo.

Her Decca producer, Milt Gabler, had trouble finding suitable songs. “She frequently wouldn’t do material that he wanted her to do,” noted her second manager, Harold Jovien. “She was very difficult… She wasn’t just being stupidly obstinate; she had principles of her artistry.”

And there was a dark undercurrent of performance anxiety.

Singer Daryl Sherman analyzes Southern’s alchemy: “I can tell she worked on her material, honed it and got it the way she wanted it. I think the spontaneity came in with the integration of voice and piano. It’s an esthetic that has to do w ith valuing the lyrics of the song as much as the harmony. You can hear it in the way she colors the lyrics. Little, almost subliminal things, like putting tiny quotation marks around a word with the piano. She had the intelligence to know where to put the melody in the song—especially in relation to her voice. For example, playing the melody in the upper register to make it brighter—there are little colors she could get here and there.”

ith valuing the lyrics of the song as much as the harmony. You can hear it in the way she colors the lyrics. Little, almost subliminal things, like putting tiny quotation marks around a word with the piano. She had the intelligence to know where to put the melody in the song—especially in relation to her voice. For example, playing the melody in the upper register to make it brighter—there are little colors she could get here and there.”

Like every other nightclub performer, Jeri had to put up with chatter and noise, but she knew that working at a lower dynamic—rather than playing louder—draws listeners in.

Though she remained the in-crowd favorite in Hollywood (Dennis Hopper and Lenny Bruce heard her at the Seville; Tony Perkins and Tab Hunter caught her at the Interlude) and elsewhere, the performance discomfort just seemed to grow worse. Her inclusion on the “Birdland ’57” concert tour, though a form of jazz validation, proved a poor fit. The big halls swallowed up her subtleties.

Her last professional hurrah seems to have been a recording session with Shorty Rogers’ band in 1962. She sang “Down With Love” and “I Hadn’t Anyone Till You.” Not long after that, Southern withdrew into private life, teaching voice and piano. She became the A-list piano and vocal coach in L.A., tutoring the likes of actresses Tina Louise, Jennifer Gray and Ruth Cameron Haden, and singer-pianist David Silverman.

Her last professional hurrah seems to have been a recording session with Shorty Rogers’ band in 1962. She sang “Down With Love” and “I Hadn’t Anyone Till You.” Not long after that, Southern withdrew into private life, teaching voice and piano. She became the A-list piano and vocal coach in L.A., tutoring the likes of actresses Tina Louise, Jennifer Gray and Ruth Cameron Haden, and singer-pianist David Silverman.

Alan Eichler managed performers like Anita O’Day and Hadda Brooks; he lived near Southern in Hollywood and visited her frequently. “I tried for years to get her to perform again,” he sighs. “She hesitated about singing but was willing to record a piano album.” One night he took her to see O’Day at the Vine Street Bar & Grill. At the end of the evening, the singer beckoned and Southern sat down at the piano and played a stunning, concerto-like performance of “Yesterdays.” It was her last appearance in front of an audience.

Before her death, on August 4, 1991, Southern wrote arrangements for a projected album of Arthur Schwartz songs and she collaborated with Silverman on a number of tone poems. She was also helping her friend Peggy Lee archive all of the latter’s written music. Eichler is convinced she was poised for a re-entry. “She had new headshots taken and she gave me copies,” he states. “They were good. She sent me one in a folded music manuscript—like a lead sheet but with no music written on it—and a pressed flower in there.”

And Jeri Southern, the introverted Nebraska girl who set a standard for singing and playing piano, who melted hearts under the spotlights, ultimately seemed to be happiest far from the public eye.

Excerpted from liner notes to: Blue Note, Chicago March 1956 by Jeri Southern (Uptown 795982)

Kirk Silsbee publishes promiscuously on rock, jazz and culture.