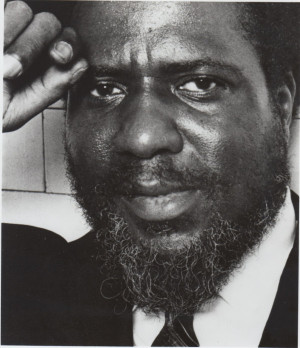

Just as James P. Johnson, George Gershwin, Fletcher Henderson and Duke Ellington took musical inspiration from New York City, it’s impossible to divorce pianist/composer Thelonious Monk’s music from Gotham.

Just as James P. Johnson, George Gershwin, Fletcher Henderson and Duke Ellington took musical inspiration from New York City, it’s impossible to divorce pianist/composer Thelonious Monk’s music from Gotham.

In Monk, the erotic and the athletic intertwine at the Savoy Ballroom, subways vibrate with propulsive rhythms, congregational choirs shake church foundations, young girls skip rope with synchronized precision and blurring velocity, street corner orators shout like secular prophets, the nighttime lights of skyscrapers form luminous patterns like so many giant dominoes, junkies dance the Apple Jack to loudspeakers outside 125th Street record stores, and the dusk light on a summertime rooftop provides solitary introspection. If genius is the ability to construct one’s own cosmos, Monk met the standard.

Dance was at the heart of Monk’s music. When the music profoundly moved him, his highest form of approval was to leave the piano bench and do a twirling, bear-like dance while the band played. The compelling rhythms seemed to take over his body. It’s not hard to listen to the rhythm section on “Well, You Needn’t” and imagine an expert tap dancer like Baby Laurence subdividing those rhythms with his own special flourishes and accents.

Monk apparently had a very lively interior world. Legend has it that on the bandstand one night (possibly at Rob Reisner’s jam sessions at the Open Door in Greenwich Village), solo space for the piano opened up on a brisk tune. Alto saxophonist Charlie Parker observed Monk eye the keyboard, as if weighing precisely where and when to begin playing, as the rhythm section blazed away. The bars of the song fell away one-by-one while Monk silently deliberated.

The entire chorus concluded without a single note being played on the piano. A bemused Parker is said to have leaned over and whispered, “Crazy, Monk.”

Monk didn’t miss much. In 1957, pianist Hampton Hawes, in the grip off narcotic addition, spent time with Monk in his New York apartment. There he grabbed a bath, was given a clean shirt, and heard a pep talk. After five years in prison, Hawes went to hear Monk at the It Club in Los Angeles in 1964. At the bar between sets, Monk didn’t appear to recognize Hawes. In Raise Up Off Me, Hawes’ autobiography, he recounts how Monk “looked over my shoulder, his elbow on the bar, staring into space the way he sometimes does…I said, ‘Monk, it’s me, Hampton.’ He kept staring past my shoulder as if he hadn’t heard, then turned his back and went into a little shuffling dance; danced a couple of quick circles around me, danced right up to me and said, ‘Your sunglasses is at my New York pad.’ And danced away.”

Monk didn’t miss much. In 1957, pianist Hampton Hawes, in the grip off narcotic addition, spent time with Monk in his New York apartment. There he grabbed a bath, was given a clean shirt, and heard a pep talk. After five years in prison, Hawes went to hear Monk at the It Club in Los Angeles in 1964. At the bar between sets, Monk didn’t appear to recognize Hawes. In Raise Up Off Me, Hawes’ autobiography, he recounts how Monk “looked over my shoulder, his elbow on the bar, staring into space the way he sometimes does…I said, ‘Monk, it’s me, Hampton.’ He kept staring past my shoulder as if he hadn’t heard, then turned his back and went into a little shuffling dance; danced a couple of quick circles around me, danced right up to me and said, ‘Your sunglasses is at my New York pad.’ And danced away.”

As Charlie Parker once noted with smiling admiration: The Monk runs deep.

As part of Universal Music’s ambitious reissue campaign of the Blue Note catalog, Kirk Silsbee has annotated three deluxe multiple-CD sets. His essays accompany comprehensive packages of the Blue Note output of Miles Davis, Clifford Brown and Thelonious Monk. The above is an excerpt from the liner notes to Monk’s Round Midnight: The Complete Blue Note Singles (1947-1952).