Read this story on The Huffington Post.

Opera goers didn’t so much descend the Metropolitan Opera House’s red staircase late Friday night as fled the house after a challenging four-hour encounter with “Boris Gudonov,” Modest Mussorgsky’s sprawling recitative-driven opera from 1869.

Opera goers didn’t so much descend the Metropolitan Opera House’s red staircase late Friday night as fled the house after a challenging four-hour encounter with “Boris Gudonov,” Modest Mussorgsky’s sprawling recitative-driven opera from 1869.

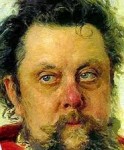

Valery Gergiev, the Mariinsky Theater conductor whose advocacy for “Boris” may have spurred the Met staging, led the vast house orchestra through a score that grants its audience nary a whistle-worthy tune. In telling the slow-moving tale of human perfidy, Mussorgsky illustrates Pushkin’s depressing libretto of pre-modern, 17th century Russia.

It’s tempting to label as Russian fanaticism Boris’s unsavory pageant of deceit, scheming, and revenge . . . but it’s too easy. In Mussorgsky’s behemoth project lies a startlingly relevant mirror of our own civilization – and an art work of disquieting universality.

Boris Gudonov’s four acts — two of which pass slower than a walk across Mother Russia — argue that selfishness and greed quash loftier human motivations.

The opera recounts a 15-year span of pre-Romanov history, when, as Moscow urban legend tells it, Tsar Boris commits a power grab, removing from the scene his key rival for the throne. This otherwise tolerable act contains a problem: the murdered rival, Dimitri, is a seven-year-old boy. Not only Boris, but the entire community grows obsessed by the blood on the Tsar’s hands.

The whopping role of Boris, an early anti-hero, declares within fifteen minutes of the opera’s start, “My soul is troubled. I’m filled with dread.”

The whopping role of Boris, an early anti-hero, declares within fifteen minutes of the opera’s start, “My soul is troubled. I’m filled with dread.”

You gotta love this guy; the film version would star Brando or Monty Clift. The Met instead featured German bass, Rene Pape, wafting and slender, in his role debut. Already a ghostly presence in his first appearance of the evening, Pape at Boris journeys inexorably through madness toward death.

Mussorgsky provides amazingly fleet x-rays of Boris’s bad company. A “Pretender” to the throne, Grigory, played by Aleksandrs Antonenko, who seeks to unseat Boris, but climbs to power on his own web of lies. The beautiful red-headed mezzo-soprano Eketerina Semenchuk, as the Polish Princess Marina, delivers a shockingly transparent aria conflating her greed for power with her lust for sex. The Holy Fool, sung by Audrey Popov, provides the opera’s moral center, singing in excellent voice.

Austrian designer Ferdinand Wogerbauer’s dry, formal, and overly austere set design—rectangles within boxes within squares within rectangles—saps passion from the evening and undercuts the fine singing. The oppressive squares give no cultural hint of curvilinear Russian culture, nor do they evoke the circles of gossip swirling round Boris.

Austrian designer Ferdinand Wogerbauer’s dry, formal, and overly austere set design—rectangles within boxes within squares within rectangles—saps passion from the evening and undercuts the fine singing. The oppressive squares give no cultural hint of curvilinear Russian culture, nor do they evoke the circles of gossip swirling round Boris.

An oversized book planted in the stage’s corner, a reminder of power of reason and intellectual thought, provides an initially clever addition, but when each character takes a turn trampling on it, it morphs into an overused stage prop.

Director Stephen Wadsworth, who inherited the Boris gig at the project’s mid-way point, had the unenviable task of picking up the pieces after the production’s original director, the innovative German director Peter Stein resigned. Stein melted down when the U.S. Consulate in Germany gave him the same bum treatment it affords most peons who apply for a U.S. visa.

Director Stephen Wadsworth, who inherited the Boris gig at the project’s mid-way point, had the unenviable task of picking up the pieces after the production’s original director, the innovative German director Peter Stein resigned. Stein melted down when the U.S. Consulate in Germany gave him the same bum treatment it affords most peons who apply for a U.S. visa.

In a snit, the maestro quit.

This human drama, worthy of “Boris Gudonov,” demonstrates that a century and a half after the opera’s creation, the hubris parade plods on.

Yes, indeed, sometimes the backstage antics, especially at this high stakes opera house, can rival the operatic drama itself. This review captured my imagination and also took me back to the “old” production, which I played years ago as a violinist in the pit at the Met.

I completely agree with the opera feeling “slower than a walk across Mother Russia” (my parents were both born there, and I can easily visualize this from their stories), although to my mind, the endless “Kovanschina” evokes that image even more powerfully. I must take issue, however, with the “nary a whistle-worthy tune.” Boris’s daughter Xenia’s lovely tune in the first “home” scene is eminently whistleable, as is the melody that comes toward the end of Marina’s scene with Grigory. I also found myself humming the fool’s theme whenever I left the opera house at the end of a “Boris” performance. But as my daughter always told me, I’m just a hopeless opera fanatic, which in the end is not so bad.

In any case, I just loved this review!