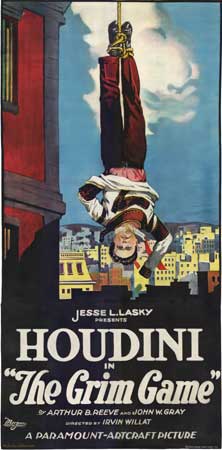

Among the many mysteries surrounding Harry Houdini is the question of whether he might have parlayed his charismatic stage persona into sound-era movie stardom. The peerless illusionist and escape artist died almost precisely a year before the release of the first feature-length talkie, The Jazz Singer. His filmography consists of five silent films, the second of which, 1919’s The Grim Game, was long considered lost.

Thanks to a couple of Houdini devotees, a film preservationist and Turner Classic Movies, the adventure drama has rematerialized in a newly restored version — all 71 minutes of it, making it a half-reel longer than previously reported.

The restoration’s world premiere, complete with a new score, capped TCM Classic Film Festival Sunday night, with movie buffs and Houdini-heads alike queuing at the Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood. It didn’t disappoint.

Houdini plays Harvey Hanford, a journalist who happens to have some mad escapologist skills. The story is essentially an inventive contraption for showcasing Houdini’s expertise. But it proceeds with a seamlessly strange logic that makes it more than a collection of ta-da moments. That’s true even in the case of the aerial stunt above Santa Monica that turned into a spectacular crash. Everyone involved survived, and director Irvin Willat shaped the incident’s footage into propulsive drama.

Houdini’s first onscreen act in the movie is to unlock a door without the key. A little later, he opens a lockbox. There will also be a bear trap to deal with, a straitjacket, and the handcuffs that his practical-joker colleagues snap onto his wrists while he dozes in the newsroom (terrifically realistic in its clutter and sense of workaday wear). He reacts to every such obstacle as an opportunity, his eyes not merely lighting up but blazing. They’re not the twinkly dreamboat eyes of Tony Curtis, who brought a working-class determination but also a glamorous delicacy to the title role in the 1953 biopic Houdini.

With his muscular physicality and mesmerizing gaze, Houdini is an unpolished and unconventional leading man. His range is no match for The Grim Game’s wonderfully expressive seasoned character actors: Thomas Jefferson, Augustus Phillips, Arthur Hoyt and Tully Marshall (who appeared in Intolerance). But he’s fascinating nonetheless, and they spark something in him.

With his muscular physicality and mesmerizing gaze, Houdini is an unpolished and unconventional leading man. His range is no match for The Grim Game’s wonderfully expressive seasoned character actors: Thomas Jefferson, Augustus Phillips, Arthur Hoyt and Tully Marshall (who appeared in Intolerance). But he’s fascinating nonetheless, and they spark something in him.

Most plot summaries of the film say it hinges on the Houdini character’s being framed, which is technically true but drastically simplified. Intriguingly, the heroic Hanford isn’t entirely innocent. As the star reporter of the Daily Call, he cares about the struggling paper’s fate and, with the help of more devious schemers, cooks up a plot to save it.

Like the strongest of Houdini’s routines, it’s an elaborate scheme that places him in temporary danger. Hanford carefully lays out self-incriminating clues in order to implicate himself in a fictitious crime and prove a larger point, still relevant today, about assumed guilt (Circumstantial Evidence was an early title for the project). But his fellow conspirators have less lofty goals, and soon the double-crossed journo is defying odds to save himself and rescue his kidnapped love interest (Danish actress Ann Forrest, conveying an unfussy resilience).

The intertitles include deliciously wry descriptions of character reactions, “Desperate thoughts of self-preservation” being a standout. (The film was written by the director and Walter Woods.) There’s humor, too, in the way Willat uses iris shots in several scenes. At the same time, he builds the tension in Hanford’s predicament through strikingly powerful images.

In an especially dark and dynamic sequence, Hanford is chased and tackled by asylum staff — a tussle that begins with nearly balletic choreography and grows almost abstract in its geometry and movement.

Brane Zivkovic’s apt if sometimes overly repetitive score, performed by a quartet of violin, cello, piano and an alluringly throaty clarinet, captures something essential about Houdini in its shifts between Old World flavor, lightheartedness and a mournful strain — and in the way it doesn’t fear silence.

Sheri Linden is a Los Angeles-based film critic.

photo credit: Twin Lens Film, Turner Classic Movies