One of the most prodigious female artists of our lifetime, the fanciful, thought-provoking, highly humane and feminist filmmaker, Agnès Varda (1928 – 2019), received kudos, a showering of affection, and shared solace over her recent death Saturday at ARRAY360. The rich film festival, which took place at the superlative cinema-campus founded in Echo Park by Ava DuVernay, programmed two Varda gems for its closing night.

Saturday’s Varda-thon cleverly book-ended two from Varda’s 55-title canon: the filmmaker’s first directorial outing, an unacknowledged masterpiece, LA COURTE POINTE (1956) and her final film, the soon-to-open documentary (in its West Coast premiere) the wonderfully entitled career retrospective, VARDA BY AGNES (2019).

The event, hosted warmly by DuVernay herself, added to Varda’s legacy in a way she may have valued beyond kudos. By dint of DuVernay’s championing them, two relatively arcane films reached a new audience that may not otherwise have crossed their path. I was very impressed to see this, and feel that it matters.

DuVernay, who first bonded with the petite, mischievous French filmmaker on the shared stage of the Cannes Film Festival led Varda’s daughter, filmmaker Rosalie Varda, in an ‘entre-acte’ conversation. Beyond being a lauded filmmaker/producer, DuVernay hosts on TCM and conducts a good interview.

“We met in Cannes three years ago,” said Rosalie Varda. “I saw in Ava’s eyes that she loved my mother’s work. We had breakfast together, and I told her that I stopped my job to support my mother [in completing VARDA BY AGNES.] Shocking to learn, apparently even the likes of Agnes Varda scrambles for film-finishing funds. “Ava said to us, ‘I can help you.'” DuVernay became a financial backer of VARDA BY AGNES, inviting two Hollywood colleagues to join in.

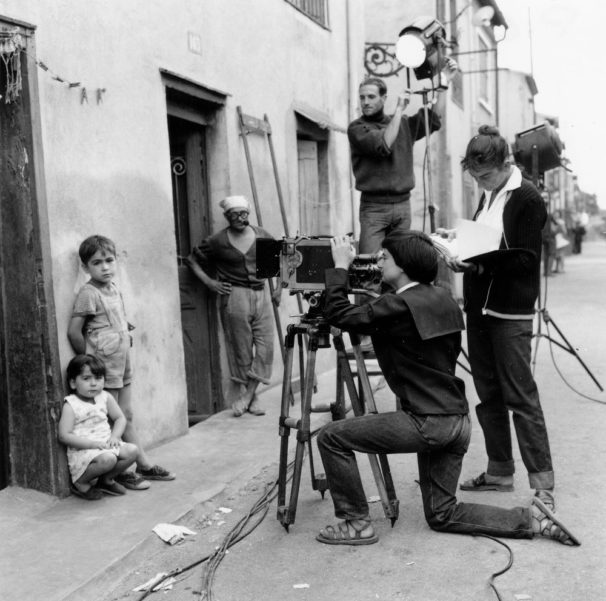

photo courtesy: The Criterion Collection

Shot on location at a fishing village in the south of France, LA POINTE COURTE tells a tale of co-existing cultures. In this regard, while it is an historic document of time and place, it is still so relevant. A handsome married couple, deep in the throes of bourgeois angst, exercise the privilege of introspection — in walks on the beach and (since it is a French film) at train stations. In a separate but not-so-equal world, a village of fishermen and their sprawling broods lead lives closer to the edge. Their days are filled by tedious work … and survival. The director shoots these noble proletariat with a loving camera (one senses a Marxist bent).

Varda, both precocious and prescient, brought a photographer’s fine eye and a big heart to this film, shooting for six weeks in late summer 1954 (ahem, I was about to be born) at a cost of $14,000. Its sumptuous black-and-white footage of gritty seaside scenes (including a lot of poverty) nearly melts from one beautifully composed frame to another. One cannot but sense the influence of her editor, the soon-to-direct Alain Resnais, who became the king of slow, long takes. Resnais and Varda gave the movie its modernist slant by implementing a voice-over soundtrack that does not spool in tandem with talking heads. In this regard, Rosalie Varda praised LA POINTE COURTE as a “highly conceptual … a radical film,” while noting its “very refined aesthetic.”

Rosalie Varda drew the crowd’s biggest laugh when DuVernay asked about her father Jacques Demy … to elicit a cagey response, “Well, he wasn’t exactly my father.” After dropping this bombshell, she explained that her mother (though not a beauty, Agnes was a fetching young woman, best described by the French expression “elle a eu du charme“) brought Rosalie, then one year-old and born out of ‘wedlock’ (why does that word have ‘lock’ in it?) to the Demy marriage as part of the deal. “My father said, ‘I have to seduce her first, or I cannot get the mother,'” said Rosalie Varda, laughing at this family mythology.

In its day, the film went unembraced by the Cahiers du Cinema crowd, and Varda’s struggle for recognition in this boy’s club was extreme. It is now considered (rightly in my opinion) as a colossus of the Nouvelle Vague. From the get-go, said her daughter, Varda did not wish to be labeled a female director, rather, a director. No woman watching her films, however, would mistake her woman’s eye, ear and soul — and often, literally, her voice. Her subject matter reflects female concerns: homelessness, education, and a woman’s right to choose. Two of her grander works, VAGABOND and THE GLEANERS & I, are so intimate and specific that had Agnes Varda not made them, no one would.

Founded in 2010 by DuVernay, ARRAY is a film collective dedicated to the amplification of images by people of color and women directors. ARRAY’s tidy and colorful campus combines courtyards, a lovely but smallish screening room, meeting rooms, a marvelous central hall for conversations, wine-and-cheese, and interviews. It’s designed just wonderfully for a space used by the public. This exceptional evening had at its heart the generous participation of DuVernay, her ebullient staff and a small army of smiling volunteers who greeted attendees.

The tone of the evening was one of adventure … one sensed an audience stretching. Unsurprisingly, it was also emotional: “My mother was born in 1928; she was a photographer by 1949; and made her first film in 1954,” said Rosalie Varda.

“We finished VARDA BY AGNES just in time for Berlin [the international film festival], three days before its mid-February screening. On March 29, my mother died. She had a beautiful long life; she had happiness, she had sadness; what a life! But there is a time to go away.”

Dance critic Debra Levine is founder/editor/publisher of arts●meme. She recently enjoyed her first byline in the New York Times.

I am so pleased. Also pleased that Ms. DuVernay, who is a powerhouse and a cinephile and a feminist and a producer/director, what else?, retweeted this story to her many followers. That is such a thrill! https://twitter.com/ava/status/1191809169591943168

I read this on my (Android) phone where it looks great!