from rosalie o’connor photo

The Boy from Kyiv: Alexei Ratmansky’s Life in Ballet, Marina Harss’s biography of one of the world’s most active choreographers, is just exactly that: a beautifully written, close examination of the many ways in which the 55-year-old artist’s work and life are intertwined. Moreover, her meticulous descriptions of his work inform those of us who haven’t seen much of it performed live just why he connects so strongly with audiences and is so highly acclaimed by critics.

Harss regularly covers dance in New York and elsewhere for the New York Times, the New Yorker, and Fjord Magazine. In 2005, when the Bolshoi Ballet was on tour in New York, early in Ratmansky’s tenure as artistic director, she went to see a mixed bill containing his The Bright Stream, a farce set on a 1930s collective farm. “It should have been terrible: anachronistic, ridiculous, stylistically retrograde. And yet it was exactly the opposite: funny and silly and sad, filled with touching details that laid bare our flawed human nature. It included a hilarious (and ironic) parade of giant vegetables, a boisterous dance for the accordionist who imagines himself to be a sort of Rudolf Valentino, performances en travesti, a man in a dog suit riding a bicycle.”

The ballet whetted Harss’s appetite to know more, much more, about the choreographer and his work and she began traveling the world to interview his family, teachers, schoolmates, friends, and the dancers and musicians he worked with. Her quest took her to Russia, to Ukraine, to Winnipeg, where he and his wife danced for several years, to Copenhagen, where he danced with the Royal Danish Ballet, and into the studios of American Ballet Theatre and other companies, where she watched rehearsals, and of course the theaters where his work was performed. With this information, and the many splendid photographs that illustrate the book, Harss has created what portrait painters might call a speaking likeness, and a richly detailed one at that.

Her title is the result of interviews conducted in Moscow, where she spoke with Ratmansky’s teachers and fellow students at the Bolshoi Academy, and learned that when he was a pupil there he was called the boy from Kyiv. Ratmansky was born in St. Petersburg on August 27, 1968, and grew up in Kyiv. He was a boarder at the Bolshoi Academy where he received his first training, and fortunate enough to spend weekends with his mother’s best friend. “Not only did she feed him,” Harss writes, “and do his laundry, but she also acted as a kind of cultural mentor, broadening his education by taking him to museums and concerts and plays.” He also spent many hours reading, novels, plays and an encyclopedia of ballet. All of this would later inform his choreography and his way of living.

He was ambitious from the start and wanted to be the best in his class, Harss learned from his first important teacher, Alexandra Mikhailovna Markeeva: “He had average physical talent”—meaning that he didn’t have ideal proportions or the natural ability to lift his legs very high—but he had a very good head!” she told me when I spoke to her in Moscow in 2017…. She pushed him.”

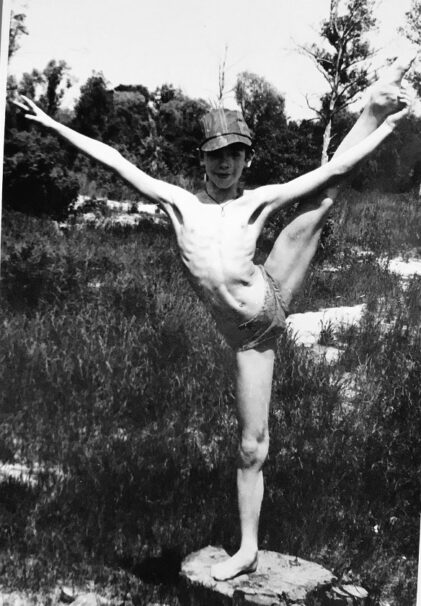

You can see the results of that pushing in this photograph, in his long leg reaching for the sky and the energy coursing through his port de bras as the supporting leg holds him steady on what appears to be a flat rock. Despite his so-called physical limitations, Ratmansky graduated with honors from the Bolshoi Academy in 1986, and then went home to Kyiv, where his first job was as a soloist with the Ukrainian National Ballet. There he met dancer Tatiana Kilivniuk, whom five years later, following a courtship that in Harss’s account resembles a romance novel set at the ballet, he married. Apart from ballet, the couple shared a free-wheeling curiosity about the world at large in general, and the evolution of ballet specifically. They continue to work together, not as dancers but as collaborators in the reconstruction of such story ballets as Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty, and Giselle, often using the Stepanov notation the way conductors use musical scores.

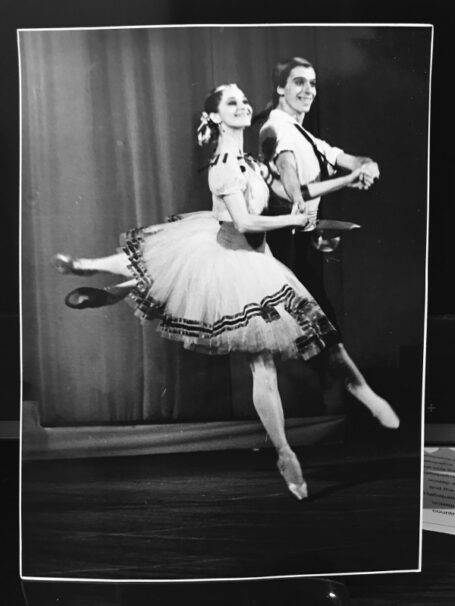

Of his performance in the latter, Harss writes, “He dances with great energy and joy, a huge smile on his face. His execution of the steps is sharp and precise, his plie deep as he rebounds joyously into the air. He takes obvious pleasure in showing off his musicality and panache, and it is clear he is having fun. At one point he gathers his feet together in a high sous-sous and holds the position for an extra moment, playing with the music, before taking off again. It creates a sense of suspension, of push and pull, and of expectation.” Note that the author’s deep musical knowledge informs her description here, just as it does throughout the book.

A few months after winning the Gold Medal at that competition, he left, alone, for Canada where he and Tatiana, who joined him later, danced with the Royal Winnipeg Ballet in a repertory Harss characterizes as a “lively mix of old and more recent classical story ballets alternating with twentieth century pieces by Antony Tudor, Frederick Ashton, John Neumeier, Twyla Tharp, George Balanchine and others.” It was here that he became well and truly hooked on Balanchine, his choreography of course, but also what he had done to streamline and modernize technique.

In 1995, the couple returned to Kyiv and the Ukrainian Ballet. Ratmansky also began his career as a choreographer in this period, participating in an evening of new works for the Bolshoi Theater, and also a smaller company in Kyiv. In 1997, both auditioned for the Royal Danish Ballet: Ratmansky was accepted but Titania wasn’t. He took the job, and shortly thereafter Tatiana learned she was pregnant. “I was thirty, I didn’t have a job, and I was kind of glad,” she told Harss.

Ratmansky spent seven years at the RDB, dancing and as Harss puts it, “making dances on the side.” Reading her account of those years, you wonder if he ever slept. Everything he made, according to Harss, whose connection to Ratmansky and his work is both clear-eyed and deeply personal, was created with the light touch of a Matisse or a Mozart. Don’t, she makes clear, look for sturm und drang in a Ratmansky ballet: Histrionics are not a part of his stagings and reconstructions of the great tragedies: Swan Lake, La Bayadere, Giselle.

In 2004, Ratmansky accepted the Bolshoi Theater’s offer of the artistic directorship of the Ballet, where he succeeded in putting the company back on the international map. He wasn’t there long; in 2008 the family of three went to New York, where Ratmansky was briefly at New York City Ballet, but landed at American Ballet Theatre as artist in residence. In his thirteen years at ABT, Ratmansky expanded the company’s repertory of evening length story ballets, and made a number of shorter ones, including a revision of his apocalyptic take on Fokine’s Firebird in which he created a role for Misty Copeland that gave what Harss calls her “languishing career a new boost.”

Harss writes:

“To Isabella Boylston, one of the Auroras, he explained that in her first entrance, which included a series of crisp staccato pas de chats, she should appear ‘like a little goat set free into the fields, jumping and running around. And when she gestured toward the prince in the Vision Scene she should do so with increasing urgency. The movement involved her shoulders and then her upper body, until one could almost hear her calling out, ‘Come to me! Come to me!’ It was through these details that the ballet began to breathe with life.”

At ABT he also headed in new directions, specifically with Serenade After Plato’s Symposium, set to Leonard Bernstein’s music of the same name. In this work, for a cast of men (there is a dramatic cameo appearance by a single woman towards the end), Ratmansky shed the bravura dancing in which he was trained in favor of an expressiveness that is more reminiscent of traditional modern dance.

Harss had just finished writing the book when Putin invaded Ukraine: she rewrote the last chapter, describing Ratmansky’s hasty exit from Moscow last February, where he was in the middle of staging the Soviet ballet The Pharoah’s Daughter on the Bolshoi. A few months later he resigned his position at ABT, on the grounds that he and the dancers had become too comfortable with each other, and needed to be challenged. He then joined New York City Ballet’s artistic staff, sharing the title of resident artist with choreographer Justin Peck. There will be plenty of challenges there, in Balanchine’s house and Harss, we can be sure, will be writing about how he meets them.

Martha Ullman West is an arts writer specializing in dance and visual arts, based in Portland, Oregon. She has written for the New York Times, the Oregonian, Dance Magazine, Dance International, Ballet Review, Dance Chronicle, the Chronicle of Higher Education Review, and currently writes for the website Oregon Arts Watch. She is the author of Todd Bolender, Janet Reed and the Making of American Ballet, which was issued by the University Press of Florida in 2021.

Apologies for the “mixed bill” error, which was mine, and no I don’t know how it happened. Mr. Ratmansky doesn’t want “Bright Stream” performed again, which grieves me since I would very much like to see it.

I’ve been eagerly awaiting this important and timely book, and this very thoughtful, detailed review only increases my anticipation. One minor correction: The Bright Stream, the work that initially caught Harss’ attention, is a full evening ballet so it couldn’t be on a “mixed bill.” It was so exciting when ABT staged its own production. One can only hope they’ll perform it again.

Martha, as the publisher of this review I want to congratulate you on your marvelous writing here.

With thanks,

Debra Levine