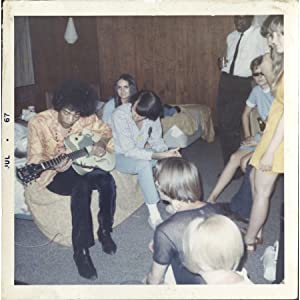

(right) with Michelle Phillips & Mama Cass Henry Diltz/ from “Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child”

ed note: This excerpt from “Jimi Hendrix: Voodoo Child” by Harvey Kubernik & Kenneth Kubernik, Sterling Books (2021) is published with permission of the authors.

In 1960s rock royalty, none wore the mantel of rock god like Jimi Hendrix. He was an unparalleled guitar virtuoso, metaphysical lyricist, musical explorer, studio innovator, and top box office draw. With his electric hair and sartorial style out of the Arabian Nights, he was a swashbuckling pirate, space cowboy or psychedelic Edwardian. Even in an era of outré fashion, Hendrix’s look was transcendental.

His celebrity and artistic capital didn’t come cheaply. He filled stadiums and sold lots of albums.Though generating millions of dollars, he wasn’t seeing or enjoying much of it. Management wanted his trio act, the Jimi Hendrix Experience, to keep working, and the money to flow steady. Promoters, TV and radio shows, journalists, newspapers, musicians, fans and groupies all wanted a piece of Jimi Hendrix.

Glowing reviews for Electric Ladyland greeted 1969, but Jimi felt trapped. Recording at TTG Studios on McCadden Street in Hollywood amounted to time-wasting marathons as he struggled to create in a circus of scenesters, drug connections and “friends.” Noel Redding and Mitch Mitchell spent long, boring hours waiting to play.

Hangers-on and fair-weather friends were everywhere, but Hendrix wondered who was listening, and who really cared about his music. For a black musician who came up through the ranks of R&B, the overwhelming whiteness of his audience was a source of chagrin. He craved black acceptance, and pressure from representatives of the increasingly violent black power movement were ongoing concerns for Hendrix. He also had a drug bust in Toronto that was coming to trial.

Soul stations across the country ignored his records, and it bothered Hendrix. He told TeenSet’s Jacoba Atlas about his frustration, adding that he was working on a song dedicated to the Black Panthers. After a rambling discourse on America and race, Hendrix called for some kind of action, but didn’t articulate what—aside from “scaring some people.” In February, he told London’s New Music Express of plans to retire for a year.

That year in Los Angeles, Hendrix stayed in a rented home in Coldwater Canyon. If he wanted nightlife, he had an invisible gold card to all the clubs. Nowhere did he have more entrée than at Thee Experience, Marshall Brevetz’s psychedelic club on Sunset Boulevard. It sat at Sierra Bonita Avenue, over a mile from the gold standard Strip, with none of the star power of West Hollywood. A transplanted Miamian, Brevetz booked second-tier bands, but bent over backwards to make the room a clubhouse for musicians to sit in, get high, and gorge on his wife’s kitchen delicacies. After hours, the doors were closed to all but a few guests, who eagerly scoffed down the long-suffering Marsha’s English breakfasts.

Thee Experience opened in late March, and by May, Hendrix had dropped in and jammed. That gave the room cache, and Brevetz had a giant Hendrix head painted on the outside of the club. Its giant mouth was thrown open—right around the double front doors.More than a few people presumed that Hendrix was the actual owner. But by late December, the room closed for good.

One night, Hendrix swept into the dimly lit club with rock star bravado, but eventually relaxed. Rockin’ Foo drummer Les Brown Jr. was there. “Jimi and I used to go to an after-hours restaurant on La Cienega,” Brown says. “I don’t think he felt that he deserved all the things that had come to him. I always felt that he thought the questions he asked me were stupid. He doubted himself.”

At the Whisky a Go Go, Hendrix was polite, asking for no special attention, though occasionally he would jam. At Thee Experience, he could relax, play, or just goof. Former waitress Wendy Weatherford recalls, “Marshall’s son Michael told me, ‘I have the weirdest recollection of hanging out under a staircase, coloring in my coloring book with Jimi Hendrix.’I said, ‘Well, that’s what you used to do; Jimi used to love to go under there and draw with you.’” She adds, “The place was about soulfulness.”

John Kale was a music student when he went to the club in June. “I went to hear guitarist Larry Coryell, but my girlfriend wasn’t feeling well,” Kale says. “I liked Coryell because he was into some very different stuff. Well, Larry did his set, but my girlfriend wasn’t getting any better. I got up to take her home, and through the front door came Jorma and Jack from the Jefferson Airplane. There was this pregnant vibe and I really hated to leave. But we got out onto the sidewalk and there was a limousine–with Hendrix getting out with a guitar case!” The opening band was England’s eccentric Bonzo Dog Band. On closing night, future Knack drummer Bruce Gary sat in. Jimi joined in on “Rockalizer Baby.”

The impressive Miami band Blues Image had moved to L.A., and used Thee Experience as home base. The late drummer Joe Lala had some long talks with Hendrix, and found him “the sweetest man you’d ever want to meet. He didn’t like where he was at that time. The managers had him dressed in all of those flashy clothes, burning his guitar and sticking out his tongue—but that’s not who he was. When he came into the club, he didn’t do any of that stuff. He just sat on an amplifier and played. It was way different than what you saw on the concert stage. He was a blues guy, an R&B guy, but a genius and an innovator—real smart, but soft-spoken.”

Seventeen-year old guitarist Mark Rodney was a Hollywood kid, and knew Hendrix by sight. Before Batdorf & Rodney, the guitar duo signed to Atlantic Records, Mark got to know Hendrix. “He loved to hear me play classical guitar,” Rodney says. “He was a very mellow guy, almost effeminate. He hated all those antics he had to do onstage.”

Read part two here.

Kirk Silsbee writes about jazz and culture. He saw the Jimi Hendrix Experience three times.