The longstanding professional relationships of the Alan Broadbent Trio might indicate that the recording at hand is the result of a comfy, well-worn process. Nothing could be further from the truth. Each selection of their new album, Trio in Motion (Savant) is a journey, and the performances are travelogues that sometimes surprise the musicians as much as listeners.

If you’ve paid attention to Alan Broadbent’s discography, you know that he’s one of the most intimate and intense pianists in jazz today. No menu of licks and quotes in his playing; a Broadbent solo is all about flow and serendipity. Hear the liberties he takes with time and phrasing on “Late Lament,” the rhythmic displacement in “Lennie’s Pennies,” and the exchange between block chord passages and the single-note lines of “Lady Bird.”

Conversation figures into how the piano and bass work together. Years of probing duets with the likes of singer Sheila Jordan and pianist Kenny Barron, make bassist Harvie S an ideal collaborator for Broadbent. A piano major at the Berklee School of Music, he transferred his creativity to the bass. “We’re getting a group sound now,” Harvie asserts. “The beginning of it was on our last album, New York Notes (Savant, 2019).”

Drummer Billy Mintz and Harvie S first played together in the 1970s, doing New York gigs with guitarist Pat Metheny and percussionist David Friedman. “It was kind of a fleeting moment,” Harvie recalls, “but I always remembered him. Many years later, I was playing with Alan and he had a Lincoln Center gig. He used Billy that night, and I could hear a world of experience in his playing compared to before. He turned into a superb artist and a good composer.”

Mintz is known for his creativity. Broadbent discovered him in Los Angeles, and they quickly locked in. He appreciated that Mintz listened to the soloists and played with taste. Notice, on the close of “The Hymn,” Mintz just withdraws and leaves the air to the piano and bass. “Billy is prepared for those moments,” Broadbent notes, “because he’s always listening. He never leads me, which a lot of drummers will do. Billy waits.” Harvie S adds: “Billy is an artist, and he sees the whole of the music.”

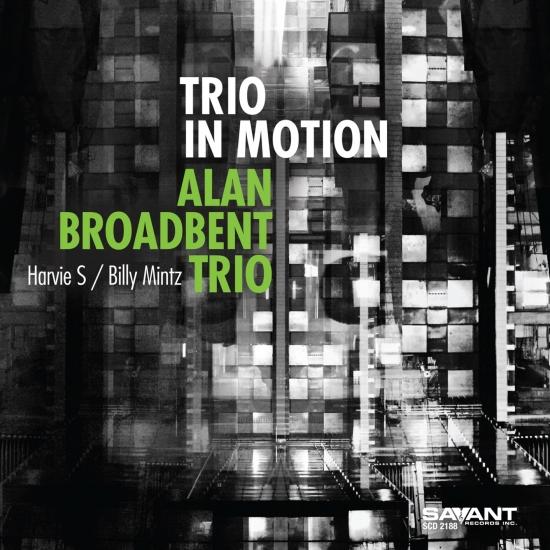

photo: juan carlos hernandez

As a student of Lennie Tristano, Broadbent spent a lot of time listening to the great recorded saxophone solos of both Lester Young and Charlie Parker–absorbing their architectural logic. It’s something he tries to impart to his students at New York University.

“People are losing this art,” Broadbent asserts, “the art of time, of the feeling that jazz gives to me and so many other people, and the art of creating a totally unique experience each time you play–especially piano players. They’re losing that Bud Powell intensity. Bud said, ‘I wish people listened to the music with the seriousness that it’s played.’ We’re all looking for the intensity; that’s where the pocket is.”

Powell’s piano innovations, his dazzling virtuosity, and his compositions are an enduring inspiration to Broadbent. Bill Evans is often cited as one of Broadbent’s prime sources, and he’d be the first to confirm that, but those influences aren’t walled off from each other. “When I was in L.A.,” Broadbent says, “I asked Lou Levy how a pianist could get close to bebop’s essence. He told me that Bird always said to listen to Bud. And Bill certainly did; listen to his New Jazz Conceptions album—it’s all Bud!”

While he has abiding musical passions and creative wellsprings—Lennie Tristano, Lester Young, Charlie Parker, Powell, Evans—Broadbent hears as much with the ears of a composer-orchestrator as he does a player. “At Berklee,” Harvie S points out, “Alan was a star—he could outplay everybody, and he was already writing for a big band.” Subsequently joining the Woody Herman Orchestra, Broadbent became the musical director, writing and arranging. Later, his work with singer Irene Kral deepened Broadbent’s understanding of the Great American Songbook. And a ten-year association with Nelson Riddle was a composition and arrangement tutorial. That alliance closed a loop of sorts: Broadbent had been listening intently to the Riddle-Frank Sinatra albums—especially In the Wee Small Hours—in his native Auckland, New Zealand. “I got to sit next to Nelson as he wrote at his little studio on Larchmont,” Broadbent says with a hint of awe.

As is his wont, Broadbent continually looks into the neglected corners of the jazz repertory and the Great American Songbook for material: seldom-heard gems like Charlie Parker’s “The Hymn,” Hoagy Carmichael’s “One Morning in May,” Paul Desmond’s “Late Lament,” the Tristano variation on “Pennies From Heaven (“Lennie’ Pennies”), John Coltrane’s “Like Sonny,” and Tadd Dameron’s “Lady Bird.” And Lil Armstrong’s “Struttin’ With Some Barbecue’—taken as a samba—is a reportorial kick in the head. “Lil was no slouch,” Broadbent affirms. “I love the absolute musicality of that song.”

“Playing with Harvie and Billy,” says Broadbent, “we’re trying to discover new ways of moving forward. We have no idea what the end result will be, but we know we’ll get through it. It’s a cliché, I know, but the process all comes down to love.”

Kirk Silsbee publishes promiscuously on jazz and culture.