The Pacific Standard Time art extravaganza that blanketed Southern California in 2011 brought much-needed, new focus to the art currents that circulated in post-World War II Los Angeles. Those surveys, as fine as they were (there were some glorious shows), implored further explorations. The Hammer’s “Now Dig This! Art & Black Los Angeles, 1960-1980” was a watershed gathering of works by many under-appreciated artists. Central to that grouping was the painter, draftsman, printmaker and teacher Charles White (1918-1979). A towering figure of Los Angeles art, he was also one of the most important national art makers of the latter 20th Century. A major White retrospective was the unspoken promise of “Now Dig This!”

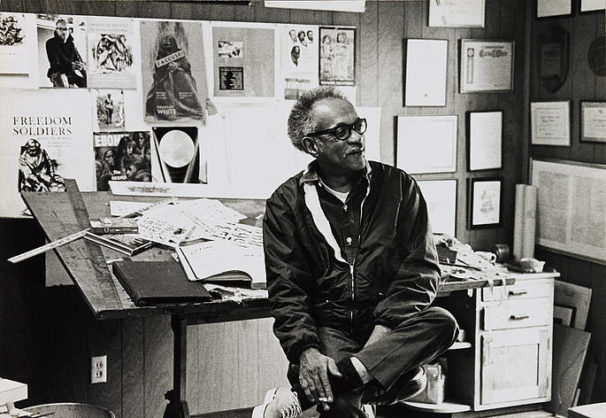

Los Angeles is the current, and final, destination of a traveling exhibit, “Charles White: A Retrospective,” organized by The Art Institute of Chicago and The Museum of Modern Art in collaboration with Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). Chicago and New York saw the show first, as White lived and worked in both cities at different times of his life. Each place saw him move through different styles and media, though his themes remained roughly consistent throughout his career.

The formative Chicago years (1918-1942) saw him at the Art Institute of Chicago. The early canvases of women at tenement window sills are social realist; they also nod to modernism in their distortions of figure and design. A W.P.A. job put him in touch with the work of Diego Rivera, with lasting impact. Even in White’s most down-trodden subjects, we look up at them, as though they stand on an unseen pedestal. During his first marriage to sculptor Elizabeth Catlett, the couple lived in Mexico where White further marinated in the works of the Mexican muralists.

White was a populist artist, and his depictions of poor and working-class black Americans made him a kind of Ben Shahn of color. Aligned with leftists and their causes, White imbued his figures with implied nobility.

Though abstraction figured into White’s images, he used it principally as texture — a decorative handmaiden to his gritty realism.

The muralist years showed White’s eagerness to expose his work as broadly as possible. He sold his work in the last 20 years of his life in Golden State Insurance-sponsored calendars and in prints that were available—and affordable — to the average person. White’s non-academic work showed his student Kent Twitchell (L.A.’s prolific muralist) a way for a realist artist to survive in an era in which the art establishment decreed figurative art to be dead.

The Los Angeles years (1956-1979) put White in contact with figures like Harry Belafonte, Dalton Trumbo and Sidney Poitier, and his work would show up in Hollywood projects. The canvases grew larger and he mostly confined his work to drawing and print-making. By then his draftsmanship was supreme. White had long since stopped needing models; he could render anything he thought of, and make his discreet distortions look utterly real.

During the Civil Rights struggle, White’s stoic, gravity-laden figures reliably played into the ‘respectability politics’ and non-violent strategy of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. After the Watts Riots of 1965, and especially during the fist-in-the-air ’70s, the quiet strength of White’s figures was seen by many young, black artists as not only passé, but counter-productive. As incendiary depictions of black figures strangled by American flags became coin-of-the-realm, White’s quietly suffering domestic workers were sneered at. His barefoot, visibly pregnant teenager in “Seed of Love,” would draw similar fire today from Planned Parenthood. But the passing years have shown that White’s images have handily withstood the test of time.

White was one of L.A.’s most important art instructors. A concurrent sister exhibit down the street at Charles White Elementary School (former site of Otis Art Institute), rounds his work from his most celebrated students. It will be discussed in a later post. In the meantime, do not miss the wonderful show at LACMA.

Kirk Silsbee publishes promiscuously on jazz and culture.

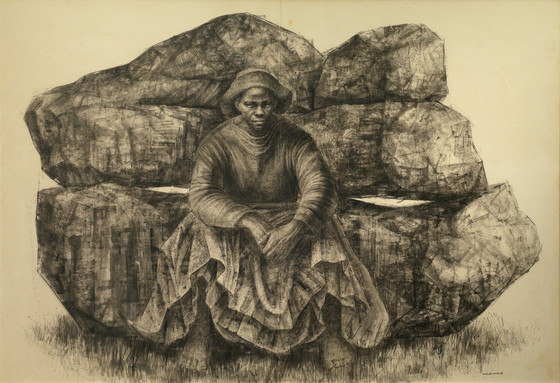

Charles White, General Moses (Harriet Tubman), 1965, ink on paper, 47 × 68 in., private collection, © The Charles White Archives, photo courtesy of Swann Auction Galleries

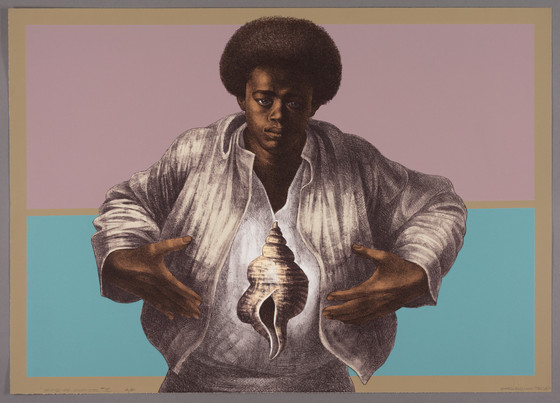

Charles White, Sound of Silence, 1978, color lithograph on white wove paper, 25 1/8 × 35 1/4 in., The Art Institute of Chicago, Margaret Fisher Fund, 2017.314, © The Charles White Archives, photo © The Art Institute of Chicago

Charles White: A Retrospective | LACMA | thru June 9