“Stanley Kubrick,” LACMA’s enormous exhibition devoted to the influential filmmaker, which closes June 30 for its only American stop, is essential viewing.

“Stanley Kubrick,” LACMA’s enormous exhibition devoted to the influential filmmaker, which closes June 30 for its only American stop, is essential viewing.

The reasons why go beyond the show’s palpably physical survey of the life and work of one of the most important directors since World War II. It provides the viewer with an entirely different experience of cinema apart from watching images move on a screen. It describes what LACMA is willing and capable of doing that it wasn’t prone to do before. It declares a fundamental difference in attitude between West Coast and East Coast museums in their view of cinema. And it happily violates all sorts of rules about art museum content.

1) Kubrick’s Last Movie

Movies, whether the celluloid or digital kind, hit us as a play of light and shadow on a screen. The lasting ones invade our subconscious and our dreams. But these ephemeral light plays are made with material stuff, an endless parade of tools. What Gilberto Perez termed “The Material Ghost” is a paradox that Kubrick understood perhaps at a more intensive level than any filmmaker before or after him, and the LACMA show (really, the Deutsches Filmmuseum show, since it originated at that fine Frankfurt institution) explains why.

Movies, whether the celluloid or digital kind, hit us as a play of light and shadow on a screen. The lasting ones invade our subconscious and our dreams. But these ephemeral light plays are made with material stuff, an endless parade of tools. What Gilberto Perez termed “The Material Ghost” is a paradox that Kubrick understood perhaps at a more intensive level than any filmmaker before or after him, and the LACMA show (really, the Deutsches Filmmuseum show, since it originated at that fine Frankfurt institution) explains why.

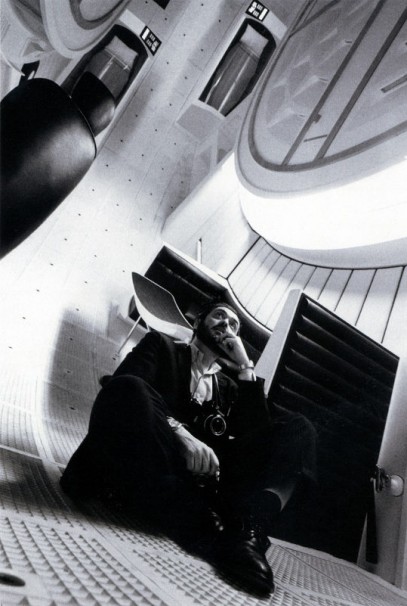

The room devoted to Kubrick’s early photography as a cub staffer for Look magazine sets up the viewer to grasp his adoration for cameras and lenses. A showcase in the gallery’s grand central room housing his favorite lenses and camera—an Arri designed to be handheld—brings objects front and center. He owned and reconfigured these tools: it can’t be emphasized enough how unusual this is for a filmmaker who worked in the studio world where unions bar directors from even touching a camera.

The room devoted to Kubrick’s early photography as a cub staffer for Look magazine sets up the viewer to grasp his adoration for cameras and lenses. A showcase in the gallery’s grand central room housing his favorite lenses and camera—an Arri designed to be handheld—brings objects front and center. He owned and reconfigured these tools: it can’t be emphasized enough how unusual this is for a filmmaker who worked in the studio world where unions bar directors from even touching a camera.

At the same time, the thoughtfully written graphic cards accompanying the displays note Kubrick’s fascination with the irrational, mythology, the paranormal, dream literature and dream analysis, all of which was funneled into “The Shining” and “Eyes Wide Shut,” two brilliant and initially misunderstood movies which form a two-part epic on the ways that psychosis, the erotic subconscious and dream can rupture marriages (or mend them). The entire Kubrick show—and the heart of its importance—is a demonstration of the tension and debate between technology and instinct, the material and shadow, reason and the irrational, the battle waged inside every movie ever made. An arranged, edited montage of the director’s objects and thoughts on this battle, the show is his last movie.

2. A Movie not on a Screen

LACMA’s version isn’t exactly the show that premiered in Frankfurt. Production designer Patti Podesta was commissioned by LACMA to redesign it for the museum’s Art of the Americas ground-floor space. What she’s done is “co-direct,” with Kubrick, a movie that’s not on a screen. Sure, there’s the requisite black box room showing a (digital) loop of extended clips from the filmography. But the heart of the show is a maze (quoting from “The Shining”) of rooms structured around themes, from Kubrick’s obsession with the color red to his conceptualization of human conflict as a chess game, to name just two. Kubrick, like Abel Gance and Sergei Eisenstein, believed in the structuring power of sequences, so each room in Podesta’s collaboration is a sequence illustrating ideas. Walking through this maze (I lost my direction more than once) creates a new kind of movie, the movie referencing itself, reminding you of the means in which movies are made while telling the story of an artist’s life. This is something new: None of the exhibits I’ve seen at the Cinematheque Francaise, for example, has done this.

LACMA’s version isn’t exactly the show that premiered in Frankfurt. Production designer Patti Podesta was commissioned by LACMA to redesign it for the museum’s Art of the Americas ground-floor space. What she’s done is “co-direct,” with Kubrick, a movie that’s not on a screen. Sure, there’s the requisite black box room showing a (digital) loop of extended clips from the filmography. But the heart of the show is a maze (quoting from “The Shining”) of rooms structured around themes, from Kubrick’s obsession with the color red to his conceptualization of human conflict as a chess game, to name just two. Kubrick, like Abel Gance and Sergei Eisenstein, believed in the structuring power of sequences, so each room in Podesta’s collaboration is a sequence illustrating ideas. Walking through this maze (I lost my direction more than once) creates a new kind of movie, the movie referencing itself, reminding you of the means in which movies are made while telling the story of an artist’s life. This is something new: None of the exhibits I’ve seen at the Cinematheque Francaise, for example, has done this.

3. LACMA Check Mates—or Does it?

A subversive streak has always lurked inside LACMA’s institutional bones—early curators weren’t afraid to display works by the two Eds (Kienholz and Ruscha) deliberately meant to scandalize patrons. But it’s become a pretty conservative place over time. “Stanley Kubrick” marks an absolute break. Art museums aren’t supposed to stage huge exhibits about filmmakers; their focus is intended to remain on masters in the plastic, handmade arts. The Kubrick show manages two things at once: It elevates the status of filmmakers to that of painters, sculptors and other visual artists; and it argues that by not examining cinema, museums have been missing a key chapter of twentieth century art. Los Angeles hasn’t seen this kind of conversation-changer since MOCA’s seminal “High and Low” show more than a decade ago.

A subversive streak has always lurked inside LACMA’s institutional bones—early curators weren’t afraid to display works by the two Eds (Kienholz and Ruscha) deliberately meant to scandalize patrons. But it’s become a pretty conservative place over time. “Stanley Kubrick” marks an absolute break. Art museums aren’t supposed to stage huge exhibits about filmmakers; their focus is intended to remain on masters in the plastic, handmade arts. The Kubrick show manages two things at once: It elevates the status of filmmakers to that of painters, sculptors and other visual artists; and it argues that by not examining cinema, museums have been missing a key chapter of twentieth century art. Los Angeles hasn’t seen this kind of conversation-changer since MOCA’s seminal “High and Low” show more than a decade ago.

LACMA does this at a time when institutions like MOMA rejected exhibiting “Stanley Kubrick” (reportedly) on the grounds that it “lacks art,” i.e., mainly a show of objects. It doesn’t matter that Podesta ties Kubrick’s oeuvre to that of Robert Rauschenberg (his paean to the space race ingeniously linked not with “2001: A Space Odyssey” but to “Dr. Strangelove”) and John McCracken (whose black monolith sculptures may have inspired “2001’s” iconic object.) The show itself is therefore its own art work, re-conceptualizing an opus and presenting it in fresh terms. With it, LACMA has checkmated every other American museum.

Now, LACMA, having placed cinema at the center of its project and hopefully inspired by Kubrick’s legacy and example, must resolve the way it shows cinema. Right now, it’s a hot mess. The dismissal of longtime film curator Ian Birnie has proven artistically disastrous: Extensive surveys and retrospectives, and a rich display of cinephilia, have given way to Hollywood social affairs overseen by programmer and once-critic Elvis Mitchell, whose superficial, patchwork approach doesn’t even represent a “program.” Rather, single screenings, geared as audience-pleasers, cater to a base of supporters in the Hollywood-centric Film Independent — producers of the Los Angeles Film Festival and the Independent Spirit Awards. (The box office uptick for these pseudo-“programs” worsens the problem.) The only real film programming at LACMA is now done by Bernardo Rondeau, who worked under Birnie and now Mitchell, and who designed the current, imaginatively conceived program accompanying the Kubrick show. LACMA can only hope to make meaningful the statement made by “Stanley Kubrick”—that cinema is key to any art museum’s identity—by ensuring that its own film programming is restored to its prior seriousness. Right now it’s a joke.

Now, LACMA, having placed cinema at the center of its project and hopefully inspired by Kubrick’s legacy and example, must resolve the way it shows cinema. Right now, it’s a hot mess. The dismissal of longtime film curator Ian Birnie has proven artistically disastrous: Extensive surveys and retrospectives, and a rich display of cinephilia, have given way to Hollywood social affairs overseen by programmer and once-critic Elvis Mitchell, whose superficial, patchwork approach doesn’t even represent a “program.” Rather, single screenings, geared as audience-pleasers, cater to a base of supporters in the Hollywood-centric Film Independent — producers of the Los Angeles Film Festival and the Independent Spirit Awards. (The box office uptick for these pseudo-“programs” worsens the problem.) The only real film programming at LACMA is now done by Bernardo Rondeau, who worked under Birnie and now Mitchell, and who designed the current, imaginatively conceived program accompanying the Kubrick show. LACMA can only hope to make meaningful the statement made by “Stanley Kubrick”—that cinema is key to any art museum’s identity—by ensuring that its own film programming is restored to its prior seriousness. Right now it’s a joke.

photos: courtesy lacma

Robert Koehler is a film critic for Film Comment, Cinema Scope and Cineaste and a contributor to Variety and Sight & Sound.