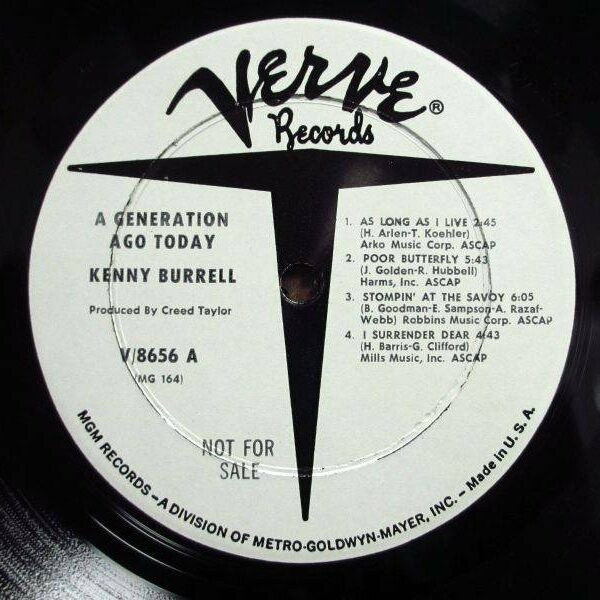

Ed. note: Universal Music continues to mine the Verve catalog for jazz treasures. arts·meme jazz writer Kirk Silsbee shares his liner notes for‘’A Generation Ago Today.’

When Kenny Burrell’s A Generation Ago Today was released in the spring of 1967, a debate was raging in jazz. It was the dawn of the Age of Aquarius, and jazz veterans were trying to figure out how to fit into a music market dominated by rock. Instrumentalists like guitarist Wes Montgomery and alto saxophonist Bud Shank were having chart success with their jazz-informed versions of pop tunes. Jazz snobs clung to traditional vehicles like “How High the Moon” and “Stardust” as the only fare acceptable for jazz, while contemporary-minded partisans — like broadcaster Johnny Magnus at KMPC in Los Angeles–applauded the jazzmen who “grooved with the times.”

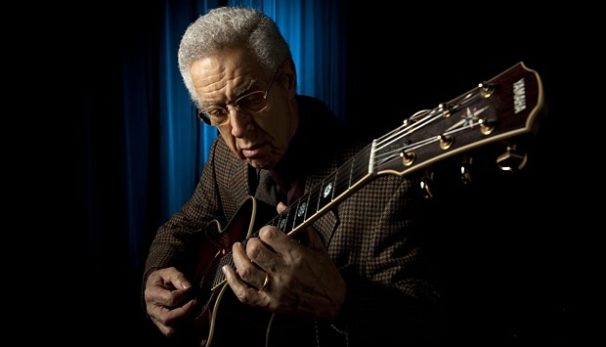

Burrell’s reputation in the jazz big leagues was based first on his protean ability to bring something special to numerous record dates with scores of leaders as diverse as saxophonists Coleman Hawkins, Illinois Jacquet, Stan Getz, Sonny Rollins, Stanley Turrentine and John Coltrane, trumpeter Thad Jones, vibraphonist Milt Jackson, pianists Tommy Flanagan, Hank Jones, organist Jimmy Smith, and singer Billie Holiday. Then, Burrell’s own albums for Blue Note set a guitar standard in the roster of that hard-swinging label. He popularized the power trio of guitar, bass and drums.

If Midnight Blue (Blue Note ‘63) announced Kenny Burrell as a leader, the brilliant Guitar Forms (Verve ’65) album showcased his virtuosity in a number of instrumental settings. Gil Evans’ expertly-crafted arrangements off-set Burrell’s versatility—from a nylon-string Spanish meditation to a funky electric blues to sublime intimacy on ballads—in ingenious ways. It remains a landmark of jazz guitar recordings.

A Generation Ago Today must have caused some marketing confusion; it was made up of material associated with Charlie Christian and Benny Goodman—all from the early 1940s. The Carnaby Street wannabe on the cover probably didn’t clarify matters. Creed Taylor, a producer with an exceptional instinct for the marketplace, supervised the sessions, and the radio-friendly times of the selections probably reflect his influence.

Christian (1916-1942) wasn’t the first to play electric jazz guitar but he was certainly the first important electric jazz guitarist. His gift for flat-picked linear improvisation and unflagging swing allowed him to engage in high-flying improvisation with clarinet icon Benny Goodman. Indeed, Christian’s addition to the Goodman Orchestra and Sextet reinvigorated the King of Swing. Though he was felled by Tuberculosis at a young age, Christian’s participation in Harlem jam sessions with Thelonious Monk and other forward-looking young players indicate that the guitarist would have been an important bebop progenitor.

His influence was pervasive among post-World War II jazz guitarists. Barney Kessel, Irving Ashby, John Collins, Mary Osborne, Jim ‘Daddy’ Walker, Jimmy Wyble, Kenny Burrell and George Benson all incorporated Christian’s incisive picking and modern chords to varying degrees in their work.

In Burrell’s case, he carried Christian’s improvisational brilliance and blues-rooted swing, but distilled through his own low-volume melodicism and unerring taste. Those attributes helped make Generation a thoroughly contemporary affirmation of swing and small band interaction.

For Generation, Burrell (born 1931) was surrounded with a clutch of New York’s finest jazz musicians: alto saxophonist Phil Woods (1931-2015) was an instrumental master who would soon be a bandleader; vibraphonist Mike Mainieri (born 1938) was beginning to make his name; bassist Ron Carter (born 1937) was a busy session player who would soon wrap up his tenure with the Miles Davis Quintet; Richard Wyands (born 1928) was a dependable and versatile pianist; and Grady Tate (born 1932) was New York’s drummer-for-all-seasons.

Like Burrell, Carter was a Detroit native, though younger. He sees a particular quality in Burrell’s playing that runs through his Detroit peers of the 1950s: “Elegance,” says Carter. “No fuss, and it all just kind of rolled off his hands. All the Detroit musicians played that way, but Kenny had a special ease by which he played. I couldn’t believe the grace and ease, how he built his lines so effortlessly.”

Rather than the O.K. Corral dynamic of the Goodman Sextet, Burrell’s tempos are mostly relaxed and the tunes are full of low-key delights: Woods’ luxuriant alto and the sensitive guitar accompaniment on “Poor Butterfly,” Burrell’s single-note phrases floating over his chords and Carter’s filigreed bass to the reflective “I Surrender Dear,” Tate’s sharp, dynamically-charged fours on “If I Had You,” and Mainieri painterly and diffused with color.

“Rose Room” served as the chordal basis for Duke Ellington’s “In a Mellow Tone.” Burrell and Woods engage in a playful volley of the two themes throughout the tune, while Carter—though playing 4/4—spins his own melodies. Wyands’ sturdy piano undergirds the swinging “Wholly Cats,” where Burrell pulls off the hat trick of being relaxed at a bright tempo.

A Generation Ago Today found favor with jazz guitar fans mostly.It wasn’t a big seller and it drifted out of print; a decade after its release the LP sold for fifty dollars among collectors.Fifty years later, the album’s superlative interaction and brilliance mark it as an unjustly neglected gem of Burrell’s discography, and ripe for renewed scrutiny.

Kirk Silsbee publishes promiscuously on rock, jazz and culture.