Despite the untimely death of its venerated, longtime host, film historian Robert Osborne, this year’s TCM Classic Film Festival isn’t likely to take on a funereal mood. Instead, it’ll probably be more like a wake.

That’s because the overarching theme of the new edition is comedy, under the theme, “Make ‘Em Laugh: Comedy in the Movies.” Osborne’s absence will be glaring; always the tallest and best-dressed man in the room, he played his familiar emcee role at the festival, as if the channel had left the TV studio and gone live. No other film festival had quite this same hook, which has steadily wooed a large turnout of regulars from the Midwest, East Coast and other locales beyond Los Angeles. Similar to the Telluride film festival, TCM Fest has turned out an affluent out-of-town crowd that often outnumbered locals.

How much of this has been due to Osborne’s presence is hard to tell, and this year will be a test of TCM Fest’s life without the face of the network.

But while this could be an interesting sidebar to the main event, the most intriguing element will be the hidden gems inside the bigger four-day (April 6-9) program—the ones that might be overlooked among the evergreen classics that fill most of the slots.

So instead of squeezing into the Thursday 6 pm screening of “Some Like It Hot,” go instead to the 6:15 pm screening of the Los Angeles premiere of Bill Morrison’s remarkable “Dawson City: Frozen Time.”

Morrison is a film artist fascinated with the beauty of decayed celluloid images, which he has transformed into a body of mesmerizing works combining fractured, nearly abstracted film frames matched with original, commissioned scores by various composers including Michael Gordon, Philip Glass and Bill Frisell. (He’s not the usual kind of filmmaker seen at TCM Classic. For one thing, he’s a radical contemporary artist. For another, he’s alive.)

In Morrison’s latest film, he recounts the discovery in 1978 of 533 reels of preserved nitrate film (including titles starring Lon Chaney Sr., Lionel Barrymore, Harold Lloyd and Douglas Fairbank) encased in permafrost under a hockey rink in the (Canadian) Yukon province town of Dawson City.

Speaking of nitrate, the process receives some significant presentations during the festival’s four days, including.

- Powell/Pressburger’s astonishing “Black Narcissus,” starring Deborah Kerr in one of the great masterpieces of color cinematography (Saturday, 9:30 pm);

- the sleek “Laura,” featuring Gene Tierney at her peak, those smooth-as-ice Otto Preminger camera moves and an iconic David Raksin score (Friday 9:30 pm); and

- the minor frolic, “Lady in the Dark,” a seldom-seen Ginger Rogers musical that looks fabulous even as it does hash to an Ira Gershwin-Kurt Weill musical score (Sunday 7:45 pm).

It’s worth noting that because of the nature of nitrate’s fragile film-chemical process, these prints can seldom be screened, and there’s no guarantee that you might be able to see them again in this condition.

In what sounds contrarian during a festival devoted mainly to comedy, look out for two movies directed by William Wyler, who has fair claim to the greatest of all Classical Hollywood directors. First, the extraordinary “Jezebel,” starring Bette Davis in one of her most supremely Bette Davis roles as a woman challenging Southern social norms (Thursday 6:30 pm). By contrast to this lavish period piece is Wyler’s compact 1951 policier, “Detective Story” (Sunday 4:30 pm), with Kirk Douglas, Lee Grant (in her screen debut, and appearing in person for the screening), William Bendix, George Macready and Gladys George. It’s a double-bill that illustrates Wyler’s gift for drawing emotional reservoirs out of great actors; like Stanley Kubrick (who also directed Douglas and Macready in “Paths of Glory” six years later), Wyler found capacities in his collaborators that they hardly knew they had, simply because no other director had pushed them so far.

In what sounds contrarian during a festival devoted mainly to comedy, look out for two movies directed by William Wyler, who has fair claim to the greatest of all Classical Hollywood directors. First, the extraordinary “Jezebel,” starring Bette Davis in one of her most supremely Bette Davis roles as a woman challenging Southern social norms (Thursday 6:30 pm). By contrast to this lavish period piece is Wyler’s compact 1951 policier, “Detective Story” (Sunday 4:30 pm), with Kirk Douglas, Lee Grant (in her screen debut, and appearing in person for the screening), William Bendix, George Macready and Gladys George. It’s a double-bill that illustrates Wyler’s gift for drawing emotional reservoirs out of great actors; like Stanley Kubrick (who also directed Douglas and Macready in “Paths of Glory” six years later), Wyler found capacities in his collaborators that they hardly knew they had, simply because no other director had pushed them so far.

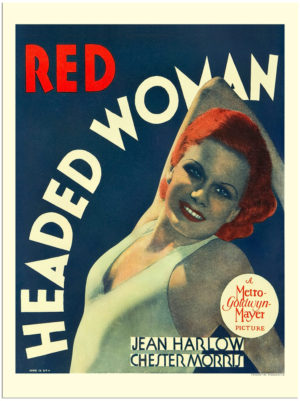

Movies before the Hays Code pushed things—like sex—pretty far for the early 1930s, and two good examples are the rare 1933 Ginger Rogers comedy, “Rafter Romance,” screening in 35mm with an intro by Leonard Maltin in the Egyptian (Friday April 7, 9 am), and “Red-Headed Woman,” written by Anita Loos and with Jean Harlow in a star-making role as a strategic seductress (Friday 7 pm).

Movies before the Hays Code pushed things—like sex—pretty far for the early 1930s, and two good examples are the rare 1933 Ginger Rogers comedy, “Rafter Romance,” screening in 35mm with an intro by Leonard Maltin in the Egyptian (Friday April 7, 9 am), and “Red-Headed Woman,” written by Anita Loos and with Jean Harlow in a star-making role as a strategic seductress (Friday 7 pm).

Earlier Friday at the Egyptian is a tasty slice of early Hollywood Lubitsch, “One Hour With You,” co-starring Jeanette MacDonald and a scintillating Maurice Chevalier (Friday April 7, 11:30 am).

During Locarno Festival’s comprehensive Lubitsch retrospective a few years ago, the re-discovery of “One Hour With You” became a highlight of that incredible survey, and it should be here. Another Lubitsch at the Egyptian later on Friday (4:30 pm) is arguably even rarer: the 1926 “So This is Paris,” one of the earliest examples of the just-forming “Lubitsch touch” and his last movie at Warners before the director’s long reign at Paramount.

Although his best movie is hardly an overlooked or obscure entertainment, the quicksilver genius of Danny Kaye was never on better display than “The Court Jester” (Saturday 9 am), a display when viewed on the big screen becomes something that seems almost impossible to the human eye. Kaye played at a pace nobody has done before or since, with a dancer’s grace and athleticism and a comic’s balancing act between precision timing and sheer madness.

One of the festival’s most interesting comedy re-discoveries is “Theodora Goes Wild” (Saturday 6:30 pm), with Irene Dunne—a superb actor in drama and some light comedy—making a real stretch in a role intended for the greatest of all screwball actors, Carole Lombard.

Even Howard Hughes made comedy, with the proof being the ultra-obscure and just-restored (by the Academy Film Archive) “Cock of the Air” (Sunday 9 am) made in 1931 to deliberately get that era’s equivalent of an X rating. The censors swooped in, but the edits forced upon Hughes have all been restored in a remarkable reconstruction project that included casting vocal actors to re-record the nearly destroyed soundtrack.

Here are three other spots on TCM’s crowded schedule grid that should be circled with a fat red marker.

- Friday 3 pm: A Conversation with Peter Bogdanovich. Along with William Friedkin, Bogdanovich remains the most enticing and fascinating raconteur about Hollywood and American moviemaking culture. He braids anecdotes with an understanding of history and a wicked sense of humor that can knock you sideways when you’re least expecting it.

- Friday midnight: John Boormann’s brawny and wild allegory-epic of social rebellion, “Zardoz,” starring a swarthy and commanding Sean Connery in definitive post-Bond mode. Unique, even in Bormann’s eclectic filmography, and with arguably the single greatest use of Beethoven in cinema history—and yes, sports fan, we’re including “A Clockwork Orange,” made three years before.

- Sunday 11:15 am: One of Douglas Sirk’s least appreciated dramas, the 1947 serial-killer thriller, “Lured,” starring Lucille Ball in fabulous form before she flipped to comedy and working with a world-class lineup of support (George Sanders, Cedric Hardwicke, Boris Karloff and Alan Mowbray).

Robert Koehler, a film critic for Film Comment, Cinema Scope, IndieWire and Cineaste, blogs about movies on arts·meme.